Abstract

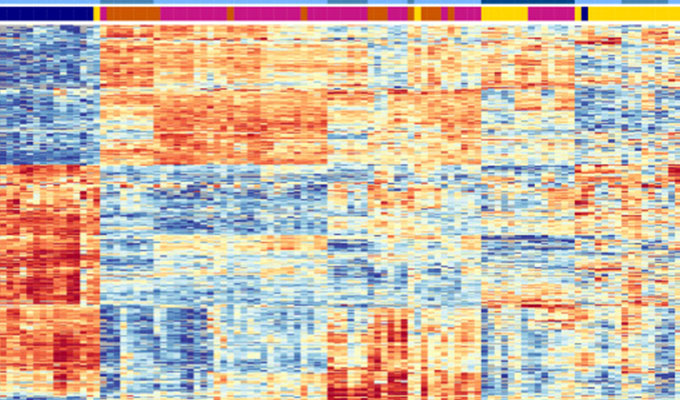

Biomolecular condensates formed via liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) are dynamic compartments critical for spatiotemporal regulation of key cellular processes, including RNA metabolism. However, under genetic mutations or chronic cellular stress, these condensates can transition into less dynamic, gel- or solid-like structures—often associated with neurodegenerative disorders.

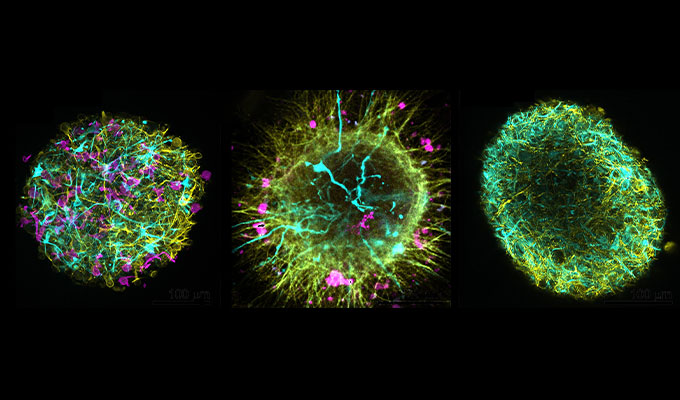

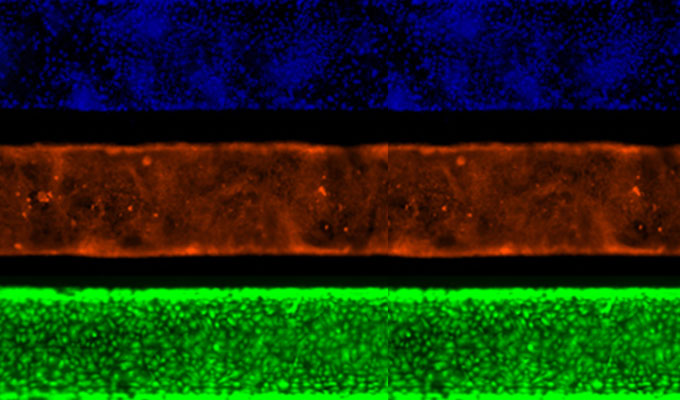

This webinar will cover a comprehensive experimental workflow to characterize the material properties and molecular dynamics of protein condensates. Topics include the expression and purification of full-length recombinant mouse prion protein (PrP) in E. coli, serving as an in vitro model system. The session will also highlight optimized protocols for fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in both in vitro and cellular settings, along with strategies for combining differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy to visualize condensate morphology and protein folding states. In addition, the application of X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy (XPCS) will be discussed as a powerful technique to assess nanoscale dynamics and condensate fluidity.

Together, these complementary techniques offer robust insights into the folding states, structural transitions, and physical behavior of proteins within condensates—providing valuable tools to better understand condensate dysregulation in disease.

Highlights

- FRAP protocols for analyzing condensate dynamics in vitro and in cells using spinning disk confocal microscopy.

- Combined DIC/fluorescence imaging for detailed visualization of condensate morphology.

- Introduction to XPCS for probing nanoscale biomolecular motion and condensate fluidity.

- Discussion on phase transitions of condensates and their relevance to neurodegenerative disease.

Speakers

Mariana J. Do Amaral, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Dr. Mariana J. Do Amaral is an Assistant Professor and Junior Research Group Leader at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Federal University of Rio de Janeir...

View more

Aline R. Passos, Ph.D.

Research Scientist, Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS), CNPEM

Dr. Aline Ribeiro Passos is a researcher at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory, part of the Centro Nacional de Pesquisa em Energia e Materi...

View more

Moderator

Yraima Cordeiro, Ph.D.

Full Professor, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Dr. Yraima Cordeiro is a Full Professor in the Department of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Federal University of Rio de ...

View more

Keywords

Biomolecular condensates, Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), Fluorescence microscopy, Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy (XPCS)

References

Do Amaral, M. J., Passos, A. R., Mohapatra, S., Freire, M. H., Wegmann, S. and Cordeiro, Y. (2025). X-Ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy, Microscopy, and Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching to Study Phase Separation and Liquid-to-Solid Transition of Prion Protein Condensates. Bio-protocol 15(8): e5277. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5277.

Do Amaral, M. J., Mohapatra, S., Passos, A. R., Lopes da Silva, T. S., Carvalho, R. S., da Silva Almeida, M., Pinheiro, A. S., Wegmann, S. and Cordeiro, Y. (2023). Copper drives prion protein phase separation and modulates aggregation. Sci Adv. 9(44): eadi7347. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adi7347

Do Amaral, M. J., M., Soares de Oliveira, L. and Cordeiro, Y. (2025). Zinc ions trigger the prion protein liquid-liquid phase separation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 753: 151489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2025.151489

Do you have a question about this webinar?

Post your question, and we'll invite the webinar speaker to respond. You're welcome to join the discussion by answering or commenting on questions ( Note: Not all questions, especially those not directly relevant to the webinar topic, may be answered by the speaker. ).

Write a clear, specific, and concise question. Don’t forget the question mark!

Tips for asking effective questions

+ Description

Write a detailed description. Include all information that will help others answer your question.

13 Q&A

In what way does a constituent in a condensate exhibit distinctive FRAP behavior compared to a constituent in cytoplasm, organelle, or membrane?

How We can proceed for the study of NPC1 protein (a lysosomal membrane protein) structural changes?

I am looking for standard Phenotype shift protocol of RAW-264.7 on induction with LPS and IL-4 and their fluorescence imaging.

Maybe an obvious question: what is the technology to see phase separation in living cells? Any technology to probe for extracellular condensates?