Advanced Search

Microinjection of Synthetic Peptides into Caenorhabditis elegans

Last updated date: Dec 29, 2025 Views: 215 Forks: 0

Hayao Ohno1, 2, *, Takanori Ida3, 4, *, and Yuichi Iino5

1Division of Material and Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Japan Women's University, Tokyo, Japan

2Department of Chemical and Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Japan Women's University, Tokyo, Japan

3Department of Veterinary Physiology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Miyazaki, Miyazaki, Japan

4Center for Animal Disease Control, University of Miyazaki, Miyazaki, Japan

5Department of Biological Sciences, School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

*For correspondence: onoh@fc.jwu.ac.jp (HO); a0d203u@ cc.miyazaki-u.ac.jp (TI)

Abstract

The genome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans encodes at least 160 predicted peptide precursor genes that can generate over 300 bioactive peptides, the functions of most of which remain unknown. Phenotypes resulting from deletion or transgenic expression of peptide genes are readily assayed, but genetic dissection of individual peptide activities is often confounded when a single gene encodes multiple peptides or when distinct peptides act redundantly. Here, we describe a protocol for direct microinjection of chemically synthesized peptides into individual worms. This approach permits investigation of the effects of an individual peptide while providing precise temporal control over peptide delivery.

Key features

- Direct injection of chemically synthesized peptides into nematodes.

In vivo effects can be analyzed within one day after peptide synthesis.

Free selection of peptides and chemical modifications.

Free selection of genetic background and timing of delivery.

Keywords: Bioactive peptides, C. elegans, In vivo experiment, Microinjection, Chemical synthesis

This protocol is used in: eLIFE 6:e28877 (2017), DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.28877.001

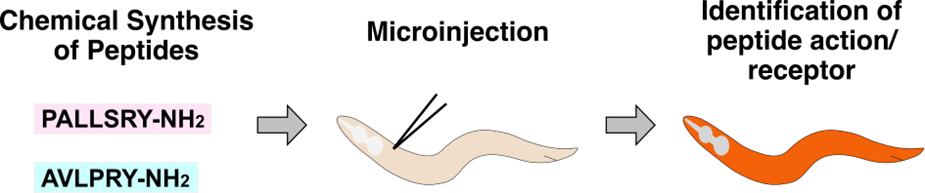

Graphical overview

Direct microinjection of chemically synthesized peptides into C. elegans. To determine the in vivo effects of a specific peptide(s) and to identify receptor mutations that abolish those effects, a chemically synthesized peptide(s) is microinjected into worms.

Background

C. elegans has a fully mapped synaptic connectome [1,2], yet understanding of how its nervous system functions remains far from complete in part because of peptide-mediated signaling between distant cells. Bioinformatic and peptidomic analyses in C. elegans have identified 160 peptide-coding genes; post-translational processing of their protein products yields more than 300 distinct peptides [3-5]. Although some of these peptides may be released from non-neuronal cells, the majority are thought to function as neuropeptides [6,7].

Genetic analysis of peptide function in C. elegans faces several practical challenges. First, individual peptide genes typically encode multiple distinct peptides; therefore, phenotypes resulting from gene deletion or overexpression do not reveal which peptide(s) are responsible. Second, multiple peptides commonly act on the same receptor [7], such that deletion of a single peptide gene often produces no detectable phenotype. Third, standard genetic manipulations that delete or overexpress peptide genes do not allow precise temporal control of peptide expression.

The protocol we describe here—direct microinjection of chemically synthesized peptides into C. elegans [8,9]—addresses these issues; it enables introduction of individual peptides, may reveal phenotypes that loss-of-function genetics miss, and allows control over the timing of peptide delivery. Furthermore, the approach can be adapted for chemically modified peptides or non‑peptidic compounds. However, injected peptide concentrations can differ substantially from endogenous levels and may produce nonphysiological effects, and some peptide actions may require specific combinations of peptides. Interpreting results is best done in conjunction with complementary approaches, such as pharmacological characterization and receptor mutant analysis.

Materials and reagents

Biological materials

1. C. elegans animals (e.g., available from Caenorhabditis Genetics Center [CGC], University of Minnesota, MN, USA)

2. An Escherichia coli strain used as a food source (e.g., HB101 or OP50, available from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center [CGC], University of Minnesota, MN, USA)

Reagents

1. Synthetic peptide of interest. Peptides can be obtained from commercial synthesis services (e.g., Scrum Inc., Tokyo, Japan). As little as 1 nmol was sufficient for the assays.

2. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Nacalai Tesque Inc., product number: 34840-34)

3. Distilled water (Nacalai Tesque Inc., product number: 14029-33)

4. Acetonitrile (Nacalai Tesque Inc., product number: 00430-83)

5. Milli-Q water (Millipore Corporation)

6. Milli-RO water (Millipore Corporation)

7. Peptone (Gibco Bacto Peptone, catalog number: 211677)

8. Sodium chloride (NaCl) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 191-01665)

9. Cholesterol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 034-03002)

10. Ethyl alcohol (Ethanol) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 09-0770)

11. Agar (TAISHO TECHNOS, catalog number: 17071902)

12. Calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2·2H2O) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 033-25035)

13. Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 131-00405)

14. Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 169-04245)

15. Disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate (Na2HPO4·12H2O) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 196-02835)

16. Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 164-04295)

17. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 168-21815)

18. Agarose (Nacalai Tesque Inc., product number: 01157-95)

19. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (BD Biosciences, 244620)

20. E. coli-seeded nematode growth media (NGM) plates (see Recipes)

21. Liquid paraffin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, catalog number: 128-04375) or Halocarbon oil 700 (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: H8898-100ML)

Solutions

1. 0.1% TFA (see Recipes)

2. HPLC B buffer (see Recipes)

3. LB liquid medium (see Recipes)

4. 5 mg/mL cholesterol (see Recipes)

5. 10 mM CaCl2

6. 10 mM MgSO4

7. 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) stock solution (see Recipes)

8. M9 buffer (see Recipes)

Recipes

1. 0.1% TFA

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

10% TFA | 0.1% | 1 mL |

Distilled water | n/a | 99 mL |

Total | n/a | 100 mL |

Store at room temperature in an amber glass bottle. Prepare 10% (v/v) TFA by diluting 100% TFA tenfold with distilled water and store at 4 °C in an amber glass bottle. | ||

2. HPLC solvent B

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

Acetonitrile | 40% | 40 mL |

Distilled water | n/a | n/a |

10% TFA | 0.1% | 1 mL |

Total | n/a | 100 mL |

Store at room temperature in an amber glass bottle. To enhance reproducibility, use graduated cylinders and glass pipettes reserved exclusively for this solution when measuring volumes. | ||

3. LB liquid medium

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

LB (Luria-Bertani) Broth Miller, Powder | 25 g/L | 2.5 g |

Milli-RO | n/a | n/a |

Total | n/a | 100 mL |

Autoclave for 20 min in a 300–500 mL flask. Store at room temperature. | ||

4. 5 mg/mL cholesterol

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

Cholesterol | 5 mg/mL | 0.5 g |

Ethanol | n/a | 100 mL |

Leave the solution in a sterilized bottle overnight to ensure complete dissolution and store at room temperature. | ||

5. 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) stock solution

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

KH2PO4 | 1 M | 136.1 g |

KOH | n/a | n/a |

Milli-Q | n/a | Up to 1 L |

Total |

| 1 L |

Dissolve in ~800 mL Milli-Q, add KOH pellets to pH 6.0, and bring volume to 1 L with Milli-Q. Autoclave for 20 min. Store at room temperature. | ||

6. M9 buffer

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

KH2PO4 | 3 g/L | 0.3 g |

Na2HPO4・12H2O | 15.2 g/L | 1.52 g |

NaCl | 5 g/L | 0.5 g |

Milli-Q | n/a | Up to 100 mL |

Total |

| 100 mL |

Sterilize by autoclaving for 20 min at 121 °C and add 100 µL 1 M MgSO4 after cooling to room temperature (final concentration is 1 mM). Store at room temperature. | ||

7. E. coli-seeded NGM plates

Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or Volume |

Peptone | 2.5 g/L | 2.5 g |

NaCl | 3 g/L | 3 g |

Agar | 17 g/L | 17 g |

5 mg/mL cholesterol | 5 mg/L | 1 mL |

Milli-RO | n/a | 800 mL |

Autoclave for 30 min in a 1 L Erlenmeyer flask. Let the NGM cool to ~65 °C. Add 100 mL of 10 mM CaCl2, 100 mL of 10 mM MgSO4, and 25 mL of 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and thoroughly mix the medium. Dispense 10 mL per 60 × 15 mm Petri dish. Leave the plates at room temperature for ~48 h under low-humidity conditions or ~72 h under high-humidity conditions, then use them or store them at 4 °C. Inoculate Escherichia coli into LB liquid medium and incubate with shaking at 37 °C overnight. Pipette 200 µL of the overnight culture onto the center of each plate, incubate the plates at room temperature for ~48 h, then use them or store them at 4 °C. | ||

Laboratory supplies

1. Sterile pipette tips

2. 50 mL conical polypropylene centrifuge tubes

3. 0.5 mL PCR single tube (SARSTEDT, catalog number: 72.735.002)

4. Glass capillary with filament (NARISHIGE, catalog number: GDC-1)

5. Capillary loading tips (Eppendorf, catalog number: 5242956003)

6. Cover Glass, 24 × 50 mm (Matsunami Glass, C018181)

7. Cover Glass, 18 × 18 mm (Matsunami Glass, C024501)

8. 1.5 mL screw-cap microtubes (SARSTEDT, catalog number: 72.692J)

9. Petri dishes, 60 × 15 mm (Greiner Bio-One, catalog number: 628161)

10. Platinum wire pick to transfer C. elegans

11. 0.22 µm filter column (Merck Millipore, catalog number: SLGV004SL)

Equipment

1. Vacuum oil pump (Thermo Scientific, model: VLP200)

2. Refrigerated vapor trap (Thermo Scientific, model: RVT4104)

3. Desiccator (Sankyo, catalog number: 85-5131)

4. Diaphragm-type dry vacuum pump (ULVAC, model: DAP-15)

5. Microcentrifuge (e.g., TOMY, model: MC-150)

6. −80 °C freezer.

7. Microwave

8. Stereomicroscope

9. Glass micropipette puller (NARISHIGE, model: PB-7)

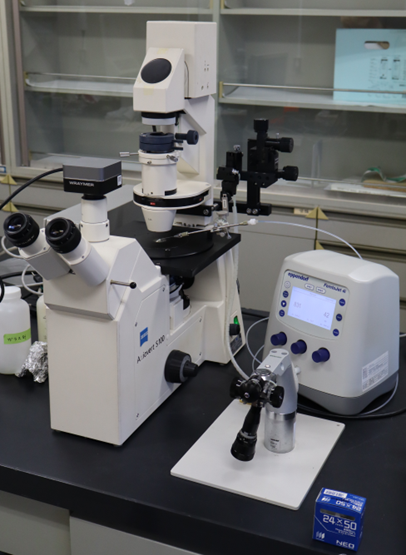

10. Inverted microscope for microinjection (ZEISS, model: Axiovert S 100 equipped with differential interference contrast [DIC] prisms, gliding table, objective 40×/0.75 EC Plan-NEOFLUAR) (Figure 1)

11. Microinjector unit (e.g., Eppendorf, model: FemtoJet 4i) (Figure 1)

12. Micromanipulator (NARISHIGE, model: MMO-4) (Figure 1)

13. Microscope Camera (optional) (Wraymer, model: WRAYCAM-VEX832) (Figure 1)

Figure 1. An example of a microinjection system set up. It comprises the inverted microscope Axiovert S 100, the microinjector FemtoJet 4i, the micromanipulator MMO-4, and the camera WRAYCAM-VEX832.

Software and datasets

1. MicroStudio (Wraymer, Version 1.9.25633.20240519) for movie acquisition from WRAYCAM-VEX832

Procedure

A. Preparation of injection pads and injection needles

1. Boil ~20 mL of 2% (w/v in water) agarose in a 100 mL glass bottle by heating in a microwave.

2. Place ~10 µL of the molten agarose onto the center of a 24 × 50 mm coverslip, then immediately place a second 24 × 50 mm coverslip on top to flatten the drop.

Note: Lowering the temperature of the agarose solution during pad formation increases the thickness of the resulting agarose pads. Although thicker pads facilitate immobilization of worms, they also exacerbate dehydration-induced damage. Determine the optimal pad thickness empirically.

3. Separate the coverslips and dry the pad at 60 °C for several hours. The injection pads can be stored in bulk at room temperature.

Note: Tracing the outline of the agarose on the back side of the coverslip with an oil‑based marker makes the pad location easy to find. Marking one corner of the coverslip (for example, the lower‑left) with the same marker and maintaining a consistent orientation prevents confusion between the front and back (Figure 2).

Figure 2. An injection pad. A droplet of liquid paraffin (described below) was placed on the injection pad (circled).

4. Mount a GDC-1 glass capillary in a micropipette puller and pull it at 65–70 °C to produce two injection needles.

Note 1: Ensure that the tip thickness and the size of its opening are appropriate. Tips that are too fine clog easily, whereas tips that are too thick do not penetrate tissue reliably. If the tip opening is too small to allow fluid flow, widen it as follows: place an 18 × 18 mm coverslip on a 24 × 50 mm coverslip, drop ~50 µL of liquid paraffin at the edge of the smaller coverslip, bring the needle tip into contact with that edge using a micromanipulator under a microscope, and gently tap the microscope stage or the needle holder.

B. Preparation of peptides and worms

1. Transfer 0.1% TFA to a 50 mL conical centrifuge tube.

Note: Pre-wash the 50 mL conical tube by adding approximately 5 mL of 0.1% TFA, vortexing, discarding the liquid, and repeating this wash three times.

2. Add 500 µL of HPLC solvent B to each of two 1.5 mL screw-cap microtubes and vortex. Spin the tubes briefly, open the caps, and remove the liquid by aspirating with a pipette tip connected to a diaphragm-type dry vacuum pump.

3. Repeat the procedure in step 2 two additional times (total of three washes). Allow the tubes to dry before use.

4. Dissolve a lyophilized synthetic peptide of interest, which can be obtained from commercial synthesis services, in 0.1% TFA to a final concentration of 10−2 M.

Note: For pipetting 0.1% TFA or the peptide solution, pre-condition each pipette tip by aspirating and discarding 0.1% TFA three times before use.

5. Transfer 10 µL (100 nmol) of the 10−2 M peptide solution into a 1.5 mL screw-cap microtube washed with HPLC solvent B in steps 2 and 3, and lyophilize as follows:

a. Close the cap, spin briefly, then loosen the cap.

b. Freeze at −80 °C for 1 hour.

c. Place the tube in a desiccator and dry overnight with a vacuum oil pump connected with a refrigerated vapor trap.

d. Remove the tube from the desiccator and tighten the cap.

Pause point: Lyophilized peptides can be stored at −20 °C.

6. Redissolve the lyophilized peptide in 1 mL of 0.1% TFA to give a 10−4 M solution.

7. Transfer 10 µL (1 nmol) of the 10−4 M peptide solution into a 1.5 mL screw-cap microtube washed with HPLC solvent B in steps 2 and 3, and lyophilize using the procedure in step 5 (substeps a–d).

Pause point: Lyophilized peptides can be stored at −20 °C.

8. Grow C. elegans worms on E. coli–seeded NGM plates to the desired developmental stage. For example, transfer L4 larvae at the white crescent stage to fresh plates using a stereomicroscope and a platinum wire pick and incubate at 20 °C for 36 h to obtain 1-day-old adult animals.

C. Microinjection

1. Dissolve the lyophilized peptide (1 nmol, see above) in 100 µL of M9 buffer to give a 10−5 M solution.

Note: Peptides can adsorb to tube walls over time after dissolution, reducing activity. Use the solution immediately or store the peptide in the lyophilized state until use.

2. Insert a 0.22 µm filter column into a 0.5 mL PCR single tube (Figure 3), load 10 µL of the peptide solution onto the filter, and centrifuge the tube at 7,000 rpm for 1 min.

Figure 3. A Filter column set in a 0.5 mL tube.

3. Remove the filter column and centrifuge the filtrate in a microcentrifuge at maximum speed for 10 min to pellet particulates to reduce the risk of capillary clogging.

4. Wipe the area around an inverted microscope for microinjection with 70% ethanol to prevent contamination.

5. Place ~100 µL of liquid paraffin onto an injection pad (see above).

6. Turn on the microinjection unit and set the injection pressures to Pi = 500 and Pc = 20. If the unit allows setting the injection volume, set it to 100 fL.

7. Load ~1 µL of the peptide solution (step 3) into an injection needle (see above) using a capillary loading tip.

8. Hold the needle vertically for ~1 min to allow bubbles to rise and escape. Confirm under a stereomicroscope that no bubbles are present at the tip.

9. Mount the needle into a needle holder attached to a micromanipulator.

10. Confirm that the micromanipulator retains sufficient travel range in all directions.

11. Position the micromanipulator so that the needle tip lies at the center of the field of view of the inverted microscope.

12. Raise the needle tip upward with the micromanipulator to make space for placement of the injection pad.

13. Transfer a worm at the appropriate developmental stage (see above) to a fresh, E. coli-free NGM plate and let the worm move around for ~20–30 s to remove adherent bacteria; eliminating bacterial carryover increases injection efficiency. Pick the worm onto the injection pad and wait until it is immobilized.

14. Place the injection pad on the stage of the inverted microscope and center the worm in the field of view.

15. Lower the needle tip using a micromanipulator and adjust focus so that both the pharyngeal region and the needle tip are sharply in view.

15. Advance the needle into the head in a direction from the midbody toward the head tip (Video 1). Inject the solution slightly posterior to the dorsal part of the pharyngeal terminal bulb until the spread diameter reaches approximately 5–10 µm (≈1/6–1/3 of the terminal-bulb diameter). The injected volume is roughly estimated to be around 100 fL, depending on the degree of vertical compression of the worm.

Note: As a control, inject peptide-free M9 buffer (vehicle) or an unrelated peptide. The injection site need not be restricted to the head; select a location that is not far from the putative receptor cells and unlikely to influence the phenotype of interest.

Video 1. Microinjection. This video shows the injection of a peptide-containing solution into the head region of a worm. To facilitate visualization, the injection solution was stained with bromophenol blue, and a slightly larger volume than used in our standard protocol was delivered.

16. While viewing under a stereomicroscope, apply 1 µL of M9 buffer to the worm and confirm detachment and movement.

D. Phenotype analysis

1. Transfer injected worms to E. coli-seeded NGM plates using a stereomicroscope and a platinum wire pick.

2. After incubation at 20–23 °C for an appropriate interval, assess the phenotype of interest. The latency to detectable peptide effects depends on the peptide and the phenotype; for example, LURY‑1–mediated modulation of pharyngeal pumping and egg‑laying behavior is apparent 3–4 hours after microinjection [8].

Validation of protocol

This protocol has been used and validated in the following research article:

Ohno et al. [8] “Luqin-like RYamide peptides regulate food-evoked responses in C. elegans”. eLife (Figure 5A,B, Figure 5—figure supplement 1C–D).

Raw data that support the findings of the article are available at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Ohno-2017-elife/5362588/2.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Conceptualization, H.O., T.I, Y.I.; Investigation, H.O., T.I.; Writing—Original Draft, H.O., T.I.; Writing—Review & Editing, H.O., T.I, Y.I.; Funding acquisition, H.O., T.I, Y.I.; Supervision, T.I, Y.I.

Funding sources: This work was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI 23K05644 and grants from the Mitsubishi Foundation, the Lotte Foundation, the Koyanagi Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, the G-7 Scholarship Foundation, the Mishima Kaiun Memorial Foundation to HO.

The protocol is based on the publication “Luqin-like RYamide peptides regulate food-evoked responses in C. elegans” (Ohno et al., 2017).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. White, J. G., Southgate, E., Thomson, J. N. and Brenner, S. (1986). The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 314(1165): 1–340. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1986.0056.

2. Cook, S. J., Jarrell, T. A., Brittin, C. A., Wang, Y., Bloniarz, A. E., Yakovlev, M. A., Nguyen, K. C. Q., Tang, L. T., Bayer, E. A., Duerr, J. S., et al. (2019). Whole-animal connectomes of both Caenorhabditis elegans sexes. Nature 571(7763): 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1352-7.

3. Van Bael, S., Watteyne, J., Boonen, K., De Haes, W., Menschaert, G., Ringstad, N., Horvitz, H. R., Schoofs, L., Husson, S. J. and Temmerman, L. (2018). Mass spectrometric evidence for neuropeptide-amidating enzymes in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem 293(16): 6052–6063. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA117.000731.

4. Cockx, B., Van Bael, S., Boelen, R., Vandewyer, E., Yang, H., Le, T. A., Dalzell, J. J., Beets, I., Ludwig, C., Lee, J., et al. (2023). Mass Spectrometry-Driven Discovery of Neuropeptides Mediating Nictation Behavior of Nematodes. Mol Cell Proteomics 22(2): 100479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100479.

5. Watteyne, J., Chudinova, A., Ripoll-Sanchez, L., Schafer, W. R. and Beets, I. (2024). Neuropeptide signaling network of Caenorhabditis elegans: from structure to behavior. Genetics 228(3): iyae141. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyae141.

6. Ripoll-Sánchez, L., Watteyne, J., Sun, H., Fernandez, R., Taylor, S. R., Weinreb, A., Bentley, B. L., Hammarlund, M., Miller, D. M., 3rd, Hobert, O., et al. (2023). The neuropeptidergic connectome of C. elegans. Neuron 111(22): 3570–3589 e3575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.09.043.

7. Beets, I., Zels, S., Vandewyer, E., Demeulemeester, J., Caers, J., Baytemur, E., Courtney, A., Golinelli, L., Hasakiogullari, I., Schafer, W. R., et al. (2023). System-wide mapping of peptide-GPCR interactions in C. elegans. Cell Rep 42(9): 113058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113058.

8. Ohno, H., Yoshida, M., Sato, T., Kato, J., Miyazato, M., Kojima, M., Ida, T. and Iino, Y. (2017). Luqin-like RYamide peptides regulate food-evoked responses in C. elegans. eLIFE 6: e28877. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.28877.

9. Rogers, C., Reale, V., Kim, K., Chatwin, H., Li, C., Evans, P. and de Bono, M. (2003). Inhibition of Caenorhabditis elegans social feeding by FMRFamide-related peptide activation of NPR-1. Nat Neurosci 6(11): 1178–1185. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1140.

Related files

movie1.mp4

movie1.mp4  PeptideInjection.docx

PeptideInjection.docx - Ohno, H, Ida, T and Iino, Y(2025). Microinjection of Synthetic Peptides into Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-protocol Preprint. bio-protocol.org/prep2887.

- Ohno, H., Yoshida, M., Sato, T., Kato, J., Miyazato, M., Kojima, M., Ida, T. and Iino, Y.(2017). Luqin-like RYamide peptides regulate food-evoked responses in C. elegans. eLife. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.28877

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link