Advanced Search

A step-by-step protocol for crossing and marker-assisted breeding of Asian and African rice varieties

Last updated date: May 6, 2024 Views: 853 Forks: 0

A step-by-step protocol for crossing and marker-assisted breeding of Asian and African rice varieties

Yugander Arra 1,4 §, Eliza P-I. Loo 1, B.N. Devanna 1,2, Melissa Stiebner 1 & Wolf B. Frommer 1,3, §

1 Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Institute for Molecular Physiology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany;

2 ICAR-National Rice Research Institute, Cuttack 753006, Odisha, India

3 Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules, Nagoya University, Chikusa, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan

4School of Biology, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Thiruvananthapuram (IISER TVM), Maruthamala P.O., Vithura, Thiruvananthapuram-695551, Kerala, India

§ For correspondence: frommew@hhu.de, array@iisertvm.ac.in

Abstract

Improving desirable traits of popular rice varieties is of particular importance for small-scale food producers. Breeding is considered the most ecological and economic approach to improve yield, especially in the context of the development of pest and pathogen-resistant varieties. Being able to cross rice lines is also a critical step when using current transgene-based genome editing technologies, e.g., to remove transgenes. Moreover, rice breeders have developed accelerated breeding methods, including marker-assisted backcross breeding (MABB) to develop novel rice varieties with in-built resistance to biotic and abiotic stressors, grain, and nutritional quality. MABB is a highly efficient and cost-effective approach in accelerating the improvement of recipient variety by introgressing desirable traits, especially from landrace cultivars and wild rice accessions. Here we provide a detailed protocol including movie instructions for rice crossing and MABB to introgress target trait(s) of interest into the elite rice line. Further, we also highlight the tips and tricks to be considered for a successful crossing and MABB.

Key features

This protocol provides detailed information on techniques for crossing rice varieties and for breeding rice varieties with new traits

The protocol includes instructions both for making rice crosses as well as MABB

The protocol may provide beginners with detailed instructions including troubleshooting guides

Keywords: Rice, back cross-breeding, donor parent, recipient parent, gene introgression, MABB

Background

Rice is one of the most important food staples for over 3.5 billion people. Classical breeding enables the development of new varieties by trait introgression for important agronomic characters and increased tolerance/resistance to abiotic/biotic stressors. Backcross breeding uses donor and recipient parents (DP and RP, respectively); the DP carries desired traits to be introgressed into an RP, typically an elite variety. Classical breeding inadvertently introduces undesirable traits from the donor and/or the loss of beneficial RP traits. It is therefore necessary to backcross the resulting progeny, i.e., the F1generation multiple times with the RP to eliminate as much of the chromosomal segments from the DP that do not carry the trait of interest as possible. Crossovers close to trait gene loci are desirable to eliminate the chance that linked loci adversely impact the resulting variety's performance.

Developing a new rice variety through breeding takes 7-8 years, (two seasons per year, maximum 16 seasons of cultivation) (Krishnan et al., 2022). New varieties must be tested in multilocation field trials to validate trait improvements relative to parental lines before new varieties are registered, which takes another 2 years. MABB reduces this timeline to three years and reduces linkage drag from the DP (Krishnan et al., 2022). MABB introgresses loci encoding desired traits into the RP and reconstitutes the genome of RP by background selection, eliminating undesirable genomic fragments, i.e. linkage drag, from the DP. MABB uses gene-based/gene-linked molecular markers for foreground; to select the desired trait/loci from DP, background selection (to determine the percentage recovery of RP genome), and recombinant selection (to determine the presence of linkage drag) (Arra et al., 2018; Singh and Krishnan, 2016). The success of MABB depends on among other things, differentiating the genome of DP from the genome of RP. Typically, simple sequence repeats (SSRs) markers are used as polymorphic molecular markers for differentiating genomic backgrounds (Mason, 2015). SSR markers are short DNA motifs (2–6 nucleotide repeats) that exhibitvariable repeat numbers in the genome. SSRs are abundant, multi-allelic, co-dominant, hypervariable, and relatively uniformly distributed in the genome. SSR markers have become important and widely used in rice breeding (Arra et al., 2018; Ellur et al., 2016; Sundaram et al., 2008).

Apart from its application in plant breeding, crosses are an essential step for eliminating transgenes introduced via genome editing. Genome editing offers the potential to target multiple loci for providing broad-spectrum resistance, nutritional fortification, and yield improvement in crops (Eom et al., 2019; Oliva et al., 2019; Schepler-Luu et al., 2023; J. Y. Wang and Doudna, 2023). Notably, the term ‘new breeding methods’ frequently used in the context of genome editing is not an optimal choice, since it is rather an alternative for generating genetic variation, in particular, targeted modifications compared to the use of naturally occurring mutations or chemically or radiation-induced mutagenesis, while the breeding process remains in the hands of breeders and requires the technologies and experience of breeders. In countries with appropriate regulations, genome-edited crops are treated as equivalent to crops generated by classical breeding (Buchholzer and Frommer, 2023).

Material and reagents

Biological material:

Two rice parents; DP and RP, to develop new desirable rice varieties.

A. Choice of DP:

Reproductive isolation can limit the ability to cross diverse rice varieties or landraces (Kumar and Virmani, 1992; Wang et al., 2024). Incompatibility between DP and RP cross leads to sterility in subsequent crosses (Sitch, 1990). Therefore, choose a DP that is genetically compatible with the RP which produces fertile F1 seeds after cross. In rice, crosses involving indica and japonica subspecies often produce sterile seeds. Similarly, crosses between O. sativa spp. indica (RP) and the DP from a wild rice species/Oryza glaberrima are reported to show embryo abortion/sterility.

The DP should possess at least a few characters for Distinctness, Uniformity, and Stability (DUS) to the RP. DUS characters play a key role during varietal nomination and evaluation (Pourabed et al., 2015). MABB-derived lines with at least 1-2 DUS characters to the RP are desirable. The choice and variety of releases also depend on DUS characters.

Choose a DP that provides a novel resource for pest/disease resistance, stress tolerance, yield attributes, agronomic characters, or grain quality.

In most cases DP is either a landrace or a wild accession. Note that it is challenging to make a successful cross between some rice species due to crossing barriers (e.g. Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima).

B. Choice of RP:

Choose an elite RP that possesses desirable characteristics including plant phenotype, protection against biotic/abiotic factors, or utilization traits (grain and cooking quality attributes).

The improved RP with higher gain yield and better economic returns tends to have higher acceptance among large-scale farmers.

Laboratory supplies

Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture (Duchefa, catalog # M0254)

Sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # S0389)

Phytagel (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # P8169)

peqGOLD Plant DNA Mini Kit (VWR, catalog # 13-3486-02)

GoTaq G2 Green Master Mix (Promega, catalog # M7823)

Agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # A6013)

GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder, ready-to-use (Thermo Scientific, catalog # SM1334)

Equipment

Analytical and Precision Balances (Precisa Gravimetrics AG, Series 321LS, model: LS 2200C)

Laboratory reagent bottles with screw cap, 1,000 ml (Duran®, catalog # 218015455)

Benchtop pH meter, WTWTM inolab TM 7110 (Fisher Scientific, catalog # 11731381)

Magnetic stirring bars, cylindrical 25x8 mm (VWR, catalog # 442-0483)

Autoclave (Systec, model # 3850 EL)

Sterile workbench (Thermo Scientific, HeraguardTM Eco)

Petri dishes (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog # P5606-400EA)

Tissue culture vessel, Magenta™GA-7 (VWR, catalog # SAFSV8505-100EA)

Hand-held wooden cereal dehusker

Centrifuge tubes with screw cap, 15 ml (Thermo Scientific, catalog # 339650)

Permanent marker pen

Precision tweezers (VWR, catalog # 232-1220)

Precision forceps, extra sharp, curved (VWR, catalog # BOCH1940)

Growth chamber with 27 °C, 16/8 day/night photoperiod (Percival, model # CU-41L5)

Head-band Magnifying Glasses (may be advantageous for proper emasculation)

Seed paper bag (11.5 x 6 cm)

Retro floor lamp with E27 Bulb including 3 lights tree floor lamp

Plastic pots, 11x11x12 cm (Mayer shop, catalog # 722009)

Plastic tray to keep plastic pots, 50x32x6 cm (Mayer shop, catalog #749112)

Whatman filter paper (VWR, catalog # 516-0593)

Height adjustable stool, useful during emasculation

Spray bottle for water, 1000 ml (Roth, # IC8T.1)

Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher, catalog #13-400-519)

Thermocycler (Bio-Rad, model: T100TM, catalog #1861096)

EasyPhor Medi gel electrophoresis system 3GT 15x10 cm (Biozym, catalog # 615162)

Gel documentation unit (Vilber E-BOX CX5 TS)

Drying and heating cabinets with mechanical adjustment (Binder, catalog # E28)

Procedure

A. Germination and growth conditions

Dehusk the rice seeds using a small hand-held wooden cereal dehusker. Transfer the dehusked seeds into a 15 ml centrifuge tube into which add 7-8 ml of 70% ethanol. Incubate the seeds for two minutes at room temperature with shaking at 80 rpm. Discard the ethanol and add 7-8 ml of 4% sodium hypochlorite into the tube followed by 5 minutes of incubation at room temperature with shaking at 80 rpm. Discard the bleach solution and rinse the seed repeatedly with sterile water until no traces of bleach are noticeable. Finally, air-dry the sterilized seeds on sterilized filter papers on a clean workbench for 15-20 mins.

Transfer the dry sterilized rice seeds onto Petri dishes containing autoclaved half-salt strength Murashige and Skoog salt (½ MS) media supplemented with 1% sucrose (Table 1). Germination in Petri dishes generally improves germination efficiency. To start seed germination, incubate the seeds (on the petri dishes) in a plant growth chamber at 27 ℃ under dark conditions for three days. After three days, transfer germinated seeds into a tissue culture vessel, Magenta™GA-7 filled with 50 ml of ½ MS media and incubated at 27 ℃ with 16 hours light/8 hours darkness for six days. After six days, transfer the seedlings to 11x11x12 cm (L x B x H) pots filled with soil and grow under greenhouse conditions (28 ± 1 ℃; relative humidity between 60-80%) until the booting stage. Water regularly and apply fertilizers as required (Luu et al., 2020). Remove old and/or dried leaves, if present, to avoid hindrance during the crossing process.

B. Emasculation:

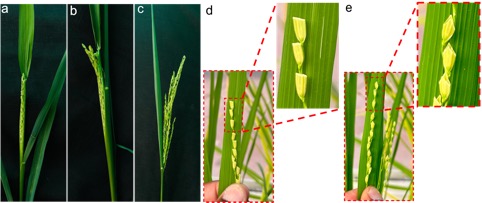

The ideal criteria for emasculation are, i) plants reached the post-booting stage, ii) show healthy panicles, iii) have no obvious signs of anthesis yet, and iv) floral organs (stigma and stamen) are still located inside the lower half of the spikelet (Figure 1).

Day 1: Spikelet opening leading to anthesis is triggered by high light intensity and humidity. Therefore, the plant growth conditions, including light intensity, temperature, and humidity should be taken into consideration when deciding the appropriate time for emasculation. It is recommended to perform emasculation either in the early morning hours (5-7 am) or early evening hours (5-7 pm). Carefully inspect rice plants for panicles with more than 50% exsertion (panicle exsertion: the distance between the leaf cushion of the flag node and the neck-panicle node; Figure 2). Correct selection of panicles is key to avoiding self-pollination. Remove the leaves surrounding the panicle, except the flag leaf, to prevent interference during the crossing. Remove young spikelets at the base of the panicle and flowered spikelets in the upper part of the panicle to achieve the optimum number (50-60) of spikelets per panicle (Movie 1). For emasculation, it is recommended to cut individual spikelets at a 35-40 degree angle just above the anthers with a pair of sterile scissors. Be careful not to damage the stigma while cutting the spikelet (Movie 2). Carefully remove each stamen (six stamens in total) from a rice spikelet using sharp tip forceps. Do not damage or break the anthers in the spikelet to avoid pollen contamination, hence self-fertilization. It is important to emasculate all the flowers in the panicle- a single anther is sufficient to self-pollinate the entire panicle.

C. Dusting and bagging:

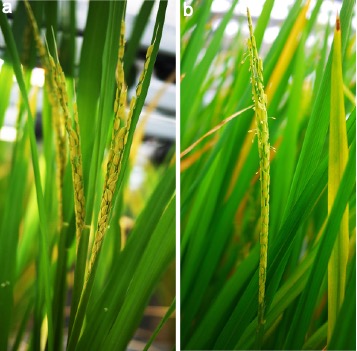

The DP plants with 30-50% of flowering panicles should be used as a source of anthers for dusting.

While carrying out the crosses in greenhouse conditions, care should be taken to position the recipient and the donor plants in such a way that the flowers of these plants are at similar heights for ease of crossing. The inflorescence or panicle of DP plants close to flowering was exposed to high light intensity (>400 µE m-2 s-1) by lowering the height of the overhead light source for 15-30 minutes to encourage flowering. Exposure to high light intensity also increases the microclimate temperature of the panicle to 30-40℃. Inflorescence with flowers with anthers at the stage of dehiscence should be used for dusting on emasculated panicles of the RP (Figure 3; Movie 3). It is important to begin dusting from the top of the emasculated panicle and slowly slide the DP panicle down the RP panicle with a gentle stroke. Immediately after dusting, cover the panicle with pre-labeled white paper bags, (important information on labels: name of the cross, date, and filial (F) generation). Depending on the availability of anthers, dusting can be repeated with the same panicle on the same or the next day to increase the percentage seed set. Tip: use a flag leaf to support the paper bag as florets are not supposed to be folded after the crossing.

Day 2-6: Provide plants with optimal growth conditions.

Day 7: If desired, one can observe the seed set one week after dusting. Gently remove the paper bag from the panicle. Healthy, immature, greenish-colored seeds are typical. The percentage seed set can be calculated by a ratio of filled to unfilled spikelets. Keep in mind to re-bag the panicle with the paper bag.

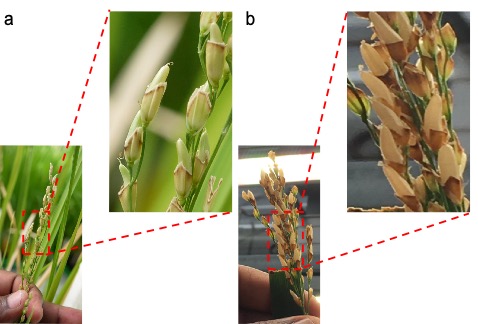

Day 15: Since the spikelets were trimmed, mature seeds could develop without husk (Figure 4a). Dried lemma and palea contribute to the light or dark yellow coloration of the husk. Since developing seeds lack husk, care should be taken to keep the insects, pests, and diseases from damaging the seeds.

Day 22: All mature seeds develop a light brown color (Figure 4b).

Day 27: Seeds (F1 generation) with a maximum of 30% moisture (Yang et al., 2002) are ready for harvest (Figure 4b).

D. Seed storage

Harvested seeds need to be dried at 40 ℃ for 2 days to reduce the moisture content of the seeds to below 12%. Higher moisture content leads to seed damage due to quick degradation of nutrients, which affects seed quality, storage life, and germination. The dried seeds can be either used for germination or preserved at 4 ℃ for long-term storage.

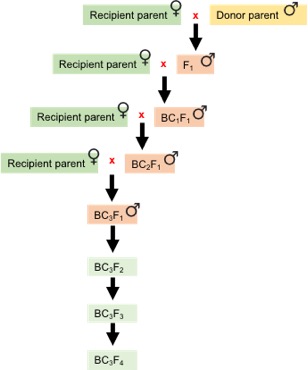

E. Marker-assisted backcross breeding (MABB)

The MABB is an application of DNA-based molecular markers to monitor and choose the target loci (foreground selection) and to accelerate the RP genome recovery (background selection) during backcrosses (Arra et al., 2018). MABB was mainly deployed to develop near-isogenic lines (NILs) with far greater precision than classical breeding. MABB accelerates the recovery of the RP genome and reduces the number of backcross generations. These plants carry the target loci in the genetic background of RP, and the percent recovery of the RP genome can be estimated in these lines (Hospital and Charcosset, 1997).

1. Foreground selection

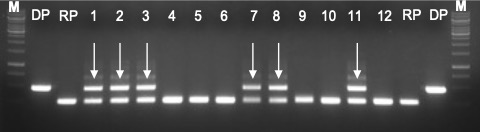

Incubate F1 seeds from the cross at 40 ℃ for 2 days to facilitate uniform germination. Germinate the F1 seeds as described in section A. Identify the positive heterozygous plants, i.e., foreground selection, and harvest approximately 100 mg of healthy leaf tissues from 25-30-day-old plants (F1 plants, and both DP and RP) with sterilized scissors from into 2 ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 3-5 glass beads. This protocol recommends the peqGOLD Plant DNA Mini Kitfor genomic DNA isolation from harvested leaf samples. Other DNA extraction kits can be adopted. Measure the genomic DNA concentration using Nanodrop (for details, see Section 4). Use gene-specific, co-dominant DNA markers (preferably SSR/SNPs) to PCR amplify target gene(s) from the isolated genomic DNA (https://archive.gramene.org/markers/microsat/). Access the hybridity of the F1 plants based on the PCR amplicon sizes compared to RP and DP. Homozygous dominant, homozygous recessive, or heterozygous for the target gene(s) of interest are typical in the F1 generation (Figure 5). Pick the heterozygous F1 plants for backcross breeding (Figure 6).

2. Background selection

Recombinant selection helps to reduce the linkage drag and to identify the breeding lines with maximum RP genome recovery (Hospital, 2001). In the present protocol, we chose a minimum of two polymorphic SSR markers (differentiating the DP and RP) for each arm of the 12 rice chromosomes. Also, we made sure that the chosen markers were at a uniform distance along the chromosome for the better recovery of the RP genome. For genome recovery calculation, we chose breeding material that was confirmed for the presence of candidate target gene(s) through foreground selection and performed PCR analysis using polymorphic SSR markers. Further, to overcome the linkage drag, we designed a set of SSR primers close to the target gene(s) loci, identified the polymorphic SSRs differentiating the RP and the DP, and used them again to screen the breeding material in the advanced (BC2F3 generation) generation for better RP genome recovery and overcome linkage drag using the software Graphical Geno Types (GGT) Version 2.0 (Van Berloo, 1999).

3. Selection of simple sequence repeats (SSRs)

More than 18,000 SSR markers have been reported for rice (McCouch, 2002; Sasaki, 2005). Information for the SSR makers is available on the GRAMENE database (https://archive.gramene.org/markers/).

Choose around 500 SSR markers distributed uniformly on all 12 rice chromosomes (with at least 1Mb distance between each marker) for PCR analysis of DP and RP.

Isolate genomic DNA from DP and RP using a DNA isolation kit or CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle, 1990).

Genotype DP and RP with selected SSRs using PCR, and identify markers showing polymorphism between DP and RP.

Choose at least 4 polymorphic SSRs between DP and RP for each rice chromosome.

Use identified polymorphic SSRs to genotype F1 up to BC2-3F2 generations to identify homozygous lines with maximum recovery of the RP genome (> 97%).

Advance lines to BC2F4 for registration or nomination and possible varietal release.

4. Genotyping for foreground or background selection

Collect leaf samples with sterilized scissors (5-8 cm long) from 25-30 days-old individual breeding plants in 2 ml microcentrifuge tubes.

Isolate genomic DNA from collected leaf samples using an available plant DNA isolation kit or CTAB method.

Measure the concentration of genomic DNA with Nanodrop and adjust the concentration to 10ng/μl.

Prepare PCR master mix (10 μl volume) with 1 μl of template DNA (10ng/μl), 0.5 μl of each primer (5 mM of each gene-specific primer solution), 5 μl of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, #M7823) and 3 ul of nuclease-free water.

Run a PCR with the following thermal profile. Initial denaturation at 95 oC for 3 minutes, followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 oC for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 oC for 30 seconds, and primer extension at 72 oC for 1 minute (1 kb/minute). The final extension is at 72 oC for 5 minutes.

Confirm the presence or absence of targeted genes via electrophoresis.

Take a photograph of the gel with a gel documentation unit, and record the data for the presence of the gene (using gene-specific markers), and also the allelic nature of these genes based on the fragment size.

For background selection, use the SSR marker data generated for each breeding line and calculate the RP genome recovery using the software Graphical Geno Types (GGT) Version 2.0 (Van Berloo, 1999).

F. Tips and tricks

For beginners, start with a bold grain shape (length to breadth ratio value, <2.0 mm) rice genotype/cultivar and practice removing anthers (emasculation) before attempting a major crossing program. It is more challenging to remove anthers from fine grain and medium slender gains.

Use the headband magnifier to facilitate observation for better emasculation

Best to remove at least the top 3-5 spikelets from each secondary branch and remove anthers with forceps to avoid anthesis and self-pollination.

Try to cut the spikelet with an upright triangle shape from both sides of the spikelet as it facilitates the opening of the spikelet and emasculation.

Choose rice DP plants with 30-40% flowering for anthers.

Spray the panicles with water before moving them to high light intensity to facilitate fast anthesis.

After dusting, it is best practice to clean and remove old, dried leaves from the base of the plant. Dried leaves serve as a physical contact for ants and insects which will damage the early-stage green embryos developed after a successful cross.

Monitor crossed panicles regularly for insects and ants both on the panicle or inside the bag covering the panicle.

Try to keep crossed plants in a clean area and fill the pots or tray with water to the maximum level (>95%) for good seed setting.

For fine-grain-type rice plants, use 40-50 spikelets/panicles for emasculation and dust with two flowered panicles.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (1155704), the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship (WBF), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany´s Excellence Strategy – EXC-2048/1 – project ID 390686111 (CEPLAS), and fellowships to YA by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, CEPLAS and DBT-Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship (2024), Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi, India.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

YA, EL, and WBF developed the concept. YA, DBN, and MS performed experiments. YA, EL, DBN, and WBF, wrote the manuscript. All authors have approved to approve the final version of the manuscript.

References:

Arra, Y., Sundaram, R. M., Singh, K., Ladhalakshmi, D., Subba Rao, L. V., Madhav, M. S., … Laha, G. S. (2018). Incorporation of the novel bacterial blight resistance gene Xa38 into the genetic background of elite rice variety Improved Samba Mahsuri. PLOS ONE, 13(5), e0198260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198260

Buchholzer, M., and Frommer, W. B. (2023). An increasing number of countries regulate genome editing in crops. New Phytologist, 237(1), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18333

Doyle, J. J., and Doyle, J. L. (1990). Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus, 12, 13–15.

Ellur, R. K., Khanna, A., S, G. Krishnan., Bhowmick, P. K., Vinod, K. K., Nagarajan, M., … Singh, A. K. (2016). Marker-aided incorporation of Xa38, a novel bacterial blight resistance gene, in PB1121 and comparison of its resistance spectrum with xa13+Xa21. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 29188. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29188

Eom, J. S., Luo, D., Atienza-Grande, G., Yang, J., Ji, C., Thi Luu, V., … Frommer, W. B. (2019). Diagnostic kit for rice blight resistance. Nature Biotechnology, 37(11), 1372–1379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0268-y

Hospital, F. (2001). Size of donor chromosome segments around introgressed loci and reduction of linkage drag in marker-assisted backcross programs. Genetics, 158(3), 1363–1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/158.3.1363

Hospital, F., and Charcosset, A. (1997). Marker-assisted introgression of quantitative trait loci. Genetics, 147(3), 1469–1485. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/147.3.1469

Krishnan, S. G., Vinod, K. K., Bhowmick, P. K., Bollinedi, H., Ellur, R. K., Seth, R., and Singh, A. K. (2022). Rice breeding. In D. K. Yadava, H. K. Dikshit, G. P. Mishra, and S. Tripathi (Eds.), Fundamentals of field crop breeding (pp. 113–220). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9257-4_3

Kumar, R. V., and Virmani, S. S. (1992). Wide compatibility in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica, 64, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00023540

Luu, V., Stiebner, M., Maldonado, P., Valdés, S., Marín, D., Delgado, G., … Frommer, W. (2020). Efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the elite-indica rice variety Komboka. BIO-PROTOCOL, 10(17). https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.3739

Mason, A. S. (2015). SSR genotyping. In J. Batley (Ed.), Plant Genotyping (pp. 77–89). New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1966-6_6

McCouch, S. R. (2002). Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Research, 9(6), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/9.6.199

Oliva, R., Ji, C., Atienza-Grande, G., Huguet-Tapia, J. C., Perez-Quintero, A., Li, T., … Yang, B. (2019). Broad-spectrum resistance to bacterial blight in rice using genome editing. Nature Biotechnology, 37(11), 1344–1350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0267-z

Pourabed, E., Jazayeri Noushabadi, M. R., Jamali, S. H., Moheb Alipour, N., Zareyan, A., and Sadeghi, L. (2015). Identification and DUS testing of rice varieties through microsatellite markers. International Journal of Plant Genomics, 2015, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/965073

Sasaki, T. (2005). The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature, 436(7052), 793–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03895

Schepler-Luu, V., Sciallano, C., Stiebner, M., Ji, C., Boulard, G., Diallo, A., … Frommer, W. B. (2023). Genome editing of an African elite rice variety confers resistance against endemic and emerging Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae strain. eLife, 12, e84864. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.84864

Singh, A. K., and Krishnan, S. G. (2016). Genetic improvement of basmati rice: The journey from conventional to molecular breeding. In V. R. Rajpal, S. R. Rao, and S. N. Raina (Eds.), Molecular Breeding for Sustainable Crop Improvement (pp. 213–230). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27090-6_10

Sitch, L. A. (1990). Incompatibility barriers operating in crosses of Oryza sativa with related species and genera. In: Gustafson, J.P. (eds) Gene manipulation in plant improvement II. Springer, Boston, MA, 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-7047-5_5

Sundaram, R. M., Vishnupriya, M. R., Biradar, S. K., Laha, G. S., Reddy, G. A., Rani, N. S., … Sonti, R. V. (2008). Marker assisted introgression of bacterial blight resistance in Samba Mahsuri, an elite indica rice variety. Euphytica,160(3), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-007-9564-6

Van Berloo, R. (1999). Computer note. GGT: Software for the display of graphical genotypes. Journal of Heredity, 90(2), 328–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/90.2.328

Wang, C., Yu, X., Wang, J., Zhao, Z., and Wan, J. (2024). Genetic and molecular mechanisms of reproductive isolation in the utilization of heterosis for breeding hybrid rice. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, S1673852724000298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2024.01.007

Wang, J. Y., and Doudna, J. A. (2023). CRISPR technology: A decade of genome editing is only the beginning. Science, 379(6629), eadd8643. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add8643

Yang, W., Jia, C., Seibenmorgen, T., Howell, T., and Cnossen, A. (2002). Intra-kernel moisture responses of rice to drying and tempering treatments by finite element simulation. Transactions of the ASAE, 45, 1037–1044. https://doi.org/doi: 10.13031/2013.9917

Figure 1. The rice panicle represents the floral organs inside of the spikelets. Stigma and stamen are located inside the lower half of the spikelet.

Figure 2. Different stages of rice panicles from the booting stage to emergence from flag leaf

a: No panicle exsertion; b: 40% panicle exsertion; c: >70% panicle exsertion; d: emasculated spikelet; e: cross cutting of spikelet

Figure 3. Panicles at (a) pre- and (b) post-flowering stages of individual plants.

Figure 4. Different stages of seed setting on recipient parent after pollination.

a: 15 days after pollination; b: 22 days after pollination. Insets represent the different maturity stages of rice seed after pollination.

Figure 5. Confirmation of heterozygosity in F1 generation by gene-specific markers (foreground selection). M: 1 kb Plus ladder; DP: Donor parent, 270 bp; RP: Recipient parent, 150 bp; Arrow indicates heterozygous for both parents 270/150 bp.

Figure 6. Crossing scheme adopted for marker-assisted backcross breeding.

Three backcrosses bring maximum recipient parent genome recovery into improved lines by implementing molecular markers (SSR/SNPs). BC1-3: number of backcrosses; F2-4: number of generations for advancing the population by selfing.

Table 1. ½ salt strength Murashige and Skoog medium

S. No | Ingredients | quantity/L |

1 | Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture | 2.2 g |

2 | Sucrose | 10.0 g |

3 | Phytagel | 4.0 g |

4 | pH | 5.8 |

- Frommer, W B(2024). A step-by-step protocol for crossing and marker-assisted breeding of Asian and African rice varieties. Bio-protocol Preprint. bio-protocol.org/prep2665.

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link