- Submit a Protocol

- Receive Our Alerts

- Log in

- /

- Sign up

- My Bio Page

- Edit My Profile

- Change Password

- Log Out

- EN

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Home

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

Advancing EAE Modeling: Establishment of a Non-Pertussis Immunization Protocol for Multiple Sclerosis

Published: Vol 16, Iss 3, Feb 5, 2026 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5589 Views: 10

Reviewed by: Anonymous reviewer(s)

Protocol Collections

Comprehensive collections of detailed, peer-reviewed protocols focusing on specific topics

Related protocols

A Participant-Derived Xenograft Mouse Model to Decode Autologous Mechanisms of HIV Control and Evaluate Immunotherapies

Emma Falling Iversen [...] R. Brad Jones

Apr 5, 2025 2512 Views

Analysis of Vascular Permeability by a Modified Miles Assay

Hilda Vargas-Robles [...] Michael Schnoor

Apr 5, 2025 2532 Views

PBMC-Humanized Mouse Model for Multiple Sclerosis: Studying Immune Changes and CNS Involvement

Anastasia Dagkonaki [...] Lesley Probert

May 20, 2025 3966 Views

Abstract

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a widely used rodent model of multiple sclerosis (MS), typically induced with pertussis toxin (PTX) to achieve robust disease onset. However, PTX has been shown to exert broad immunomodulatory effects that include disruption of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, altered T-cell response, and exogenous suppression of regulatory T cells, all of which are not present in human MS pathophysiology. Moreover, PTX also obscures the sex differences observed in MS, limiting the translational value of EAE models that rely on it. Given EAE’s widespread use in preclinical therapeutic testing, there is a critical need for a model that better recapitulates both clinical and immunological features of MS without PTX-induced confounds. Here, we demonstrate a non-pertussis toxin (non-PTX) EAE model in C57BL/6 mice, using optimized concentrations of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35-55) peptide. This model recapitulates hallmark features of MS that include demyelination, neuroinflammation, motor deficits, and neuropathic pain. Importantly, it retains sex-specific differences in disease onset and pathology, providing a more physiologically and clinically relevant platform for mechanistic and translational MS research.

Key features

• Establishes a reproducible clinically relevant EAE protocol in C57BL/6 mice that induces MS-like neurological deficits without pertussis toxin.

• Recapitulates hallmark MS pathology, including neuroinflammation, demyelination, axonal injury, and neuropathic pain.

• Eliminates the off-target effects of pertussis toxin, which confound GPCR-mediated signaling, T-cell responses, and neuroimmune interactions.

Keywords: Pertussis toxin (PTX)Graphical overview

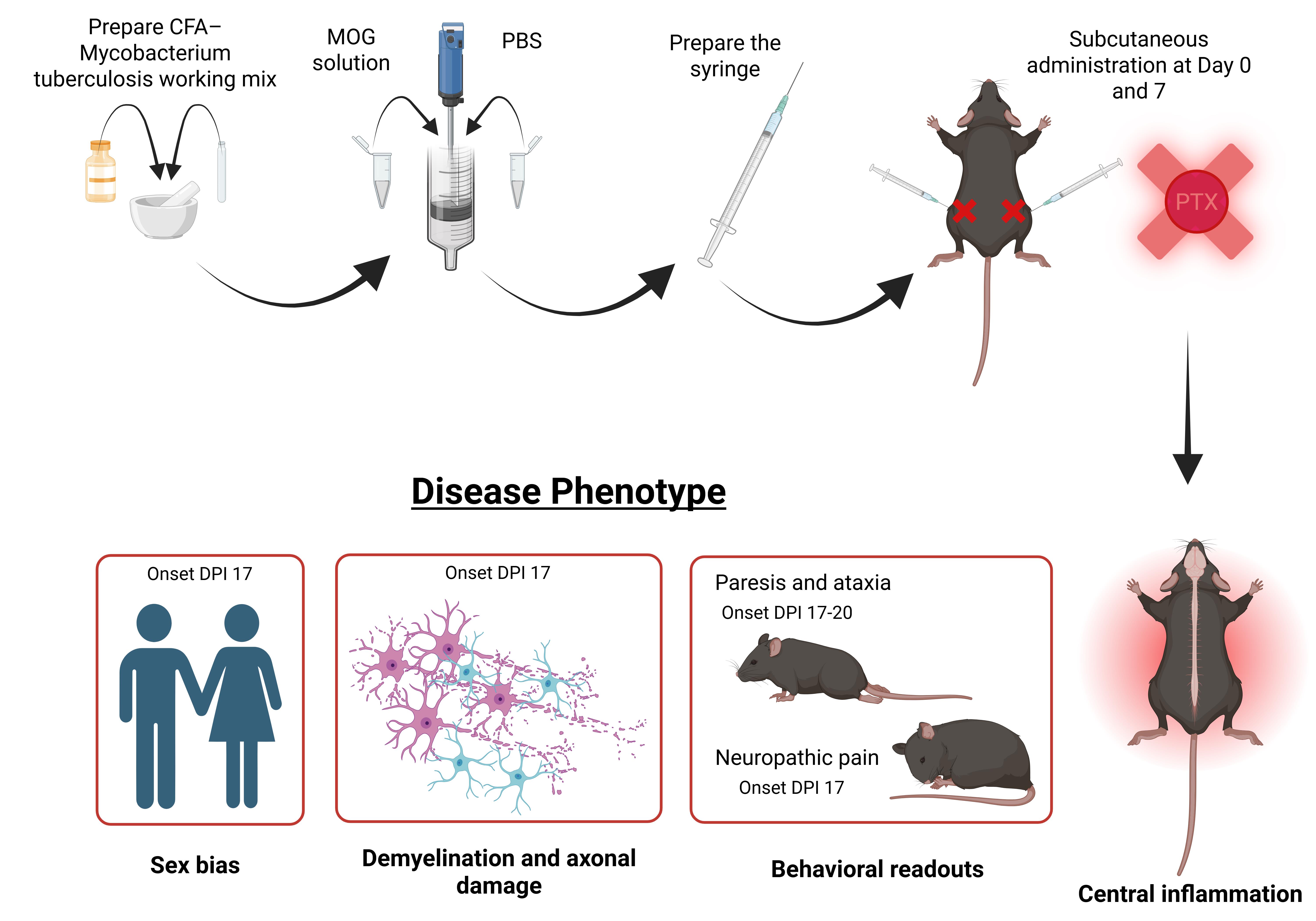

Graphical overview of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) immunization and disease phenotype manifestation without pertussis toxin. DPI: Days post immunization.

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder with over 8 million individuals diagnosed [1]. Current treatments rely on immunosuppressive disease modifying therapies; however, these therapies have limited therapeutic efficacy and significant side effects [2–4].

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a rodent model of MS extensively used in the field to investigate disease pathophysiology and advance therapeutic discovery and curative strategies [5–9]. EAE mimics key MS pathophysiology and successfully recapitulates the hallmarks of the disease—demyelination, neuroinflammation, gliosis, and axonal damage [6,9–12]. Moreover, it also replicates the two prominent symptoms of MS—neuropathic pain and motor deficits [13–15]. Most often, active EAE induction in C57BL/6 mice requires immunization with the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35-55) peptide emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) and heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis, alongside co-administration of pertussis toxin (PTX) [6,7,16].

PTX is a bacterial exotoxin that facilitates disease induction by artificially disrupting the blood–brain barrier (BBB), enabling CNS infiltration of peripheral immune cells [17,18]. However, apart from its synthetic effect on immune cell infiltration in the CNS, it also introduces several confounding variables. PTX disrupts G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling through ADP-ribosylation, complicating studies that seek to understand GPCR function in neuroinflammation and immune regulation, which is relevant given the growing recognition of GPCRs in MS pathogenesis [19–22].

PTX’s broad immunomodulatory properties extend beyond adjuvant effects. It alters the immune landscape through suppression of regulatory T cells and skews T helper responses toward pathogenic Th1 and Th17 phenotypes, which artificially exacerbates the pro-inflammatory effect of EAE pathology [23–26]. Additionally, it has also been shown to mask sex differences that are prevalent in MS pathology [27]. Together, these factors limit the translational relevance of PTX-based EAE models and warrant the use of alternative protocols that better preserve physiological immune responses.

Recent work from our lab demonstrates that EAE can be reliably induced in C57BL/6 mice without PTX, using optimized antigen and adjuvant conditions [27–31]. This non-PTX EAE model recapitulates key clinical and pathological features of MS, including motor deficits, neuropathic pain, demyelination, neuroinflammation, gliosis, and axonal loss, without relying on artificial BBB disruption. Importantly, omitting PTX reveals biologically meaningful sex-specific differences in disease onset, immune activation, and neurodegeneration that are often masked in traditional PTX-dependent EAE models [27,31].

Increase in myelin and axonal pathology, immune cell infiltration, and glial activation in the brain and lumbar spinal cord have been assessed in our model using immunohistochemistry, western blotting, and flow cytometry [27,29,30]. Moreover, in our non-PTX EAE model, females develop paresis significantly earlier than males; however, immunopathological analyses revealed heightened glial and immune activation in EAE males, mirroring the clinical trajectory of MS. Specifically, male EAE animals exhibited significantly greater CD45+ leukocyte and peripheral macrophage infiltration in the lumbar spinal cord relative to female EAE mice [27].

Given the increasing interest in modeling MS pathophysiology in a more biologically and translationally relevant manner, the non-PTX EAE model offers a powerful platform for mechanistic studies, therapeutic testing, and the investigation of sex as a biological variable. In this paper, we describe a detailed and reproducible protocol for non-PTX EAE induction in C57BL/6 mice, along with phenotypic readouts and histopathological assessments that validate the model’s utility in capturing the heterogeneity of MS.

Materials and reagents

Biological materials

1. Heat-inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Fisher Scientific, catalog number: DF3114-33-8), stored at -20 °C

2. C57BL6/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, stock number: 000664)

Laboratory supplies

1. MOG35–55 peptide (Biosynthesis, catalog number: 12668-10)

2. Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) (InvivoGen, catalog number: vac-cfa-10)

3. 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), no calcium, no magnesium (Gibco, catalog number: 14190144), pH 7.0–7.3

4. 10 and 1 mL syringes (without needles) (BD, catalog numbers: 309605 and 309628)

5. 20 G needles (precision glide hypodermic injection needle, short bevel 20 G × 1") (BD, catalog number: 305178)

6. 50 mL conical tubes (50 mL high clarity conical centrifuge tubes) (Falcon, catalog number: 14-432-22)

7. Parafilm (Thomas Scientific, catalog number: 1222J99)

8. Isoflurane (Kent Scientific, catalog number ISO-6)

Equipment

1. Small mortar and pestle (porcelain mortar and pestle sets, deep form) (Thomas Scientific, catalog number: 1201U67)

2. Tissue homogenizer (Biospec Products, catalog number: 985370-04)

3. Standard laboratory chemical fume hood

Procedure

A. Preparation of CFA stock and working solutions

Note: These steps should be conducted under a standard laboratory chemical fume hood until the mTB is mixed with the CFA.

1. Pulverize 1 ampule (100 mg) of lyophilized Mycobacterium tuberculosis using a mortar and pestle (Figure S1) for 30 s. The bacteria will start sticking to the wall of the mortar.

2. Thoroughly vortex a vial of CFA (10 mL), then pour the contents into the mortar containing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

3. Mix thoroughly using the pestle until homogeneous.

4. Transfer the resulting CFA–Mycobacterium tuberculosis mixture from step A3 back into the original CFA vial. Label this as the stock solution.

5. Prepare the working concentration as follows:

a. Vortex another vial of CFA, transfer 4 mL of CFA from this vial into a sterile 50 mL conical tube, and store at 4 °C for future use.

b. To the remaining 6 mL in the vial, add 4 mL of the CFA–Mycobacterium tuberculosis stock mixture (from step A4), bringing the total volume to 10 mL. Label this as working CFA vial.

6. Store both stock and working concentration vials at -20 °C for up to two weeks.

B. Preparation of EAE emulsion

Notes:

1. The volumes calculated here are for a total of 10 mice; prepare emulsion for two extra mice to account for handling loss.

2. These procedures can be done on a bench top, depending on institutional regulations.

1. Modify a 10 mL syringe by cutting off the plastic hub at the needle attachment site using a razor blade (Figure S2).

2. Seal the tip with parafilm and remove the plunger (Figure S3).

3. In a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, dissolve 1 mg of MOG35-55 in 100 μL of 1× DPBS to achieve a 10 mg/mL concentration of MOG35-55 solution.

4. Add the following components directly into the modified 10 mL syringe in the following order:

a. 500 μL of CFA–Mycobacterium tuberculosis working solution from step A5b.

b. 400 μL of 1× DPBS.

c. 100 μL of MOG35-55 solution from step B3.

5. Homogenize the contents using the tissue homogenizer at speed setting 6 for 1–2 min or until a stable emulsion forms. The emulsion should appear white, opaque, and viscous (Figure S4).

6. Remove the Parafilm and attach a clean, sterile 1-mL syringe (with its plunger removed) to the tip of the 10-mL syringe, maintaining both syringes in a straight alignment. Carefully reinsert the 10-mL plunger to expel the emulsion directly into the 1-mL syringe (Figure S5) at the desired volume (maximum of 1 mL).

7. Invert the 1-mL syringe to prevent the emulsion from escaping through the barrel and to expel air while retrieving the plunger.

8. Reinsert the plunger. To minimize loss of emulsion, you may position a second sterile 1-mL syringe (with its plunger removed) over the tip of the original syringe to capture any emulsion that may be displaced during plunger insertion (Figure S6).

9. Attach 20 G needles and store the prepared syringes on ice until use (can be stored on ice for 2 h).

C. EAE immunization procedure

Note: All animal procedures should be performed in accordance with institutional animal care and use protocols.

1. Anesthetize each mouse using isoflurane at 4.5% with a flow rate of 500 mL/min mixed with oxygen. Ensure the animal is anesthetized by the toe pinch test.

2. Manually restrain the animal and extend one of the hind limbs.

3. A second individual should administer 50 μL of the prepared emulsion subcutaneously into the marked hind flank (Figure S7).

4. Let go of the hindlimb and repeat the injection on the second side by extending the second hindlimb (total of 100 μL per animal).

5. Repeat the immunization after one week to boost the immune response.

6. Behavioral assays can begin 15 days post-first immunization (Figure 1) and biochemical assays can begin 15–17 days post-first immunization.

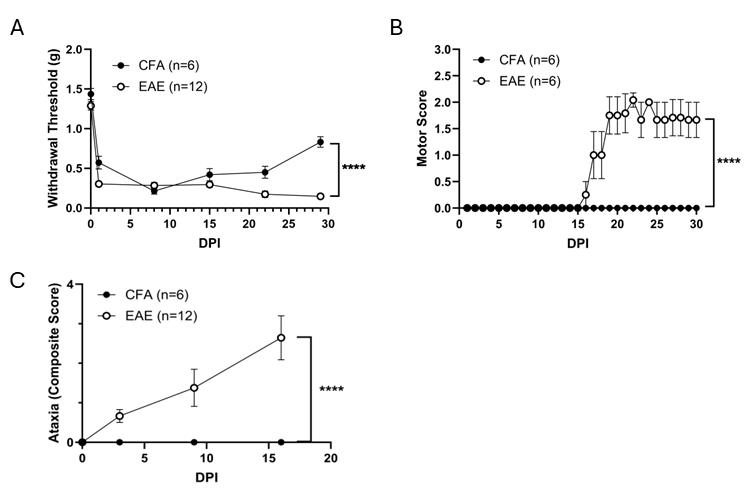

Figure 1. Non–pertussis toxin (PTX) immunization develops multiple sclerosis (MS)-associated behavioral phenotype. Male mice were immunized with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) at DPI (days post immunization) 0 or with CFA (control). (A) Mechanical allodynia was evaluated weekly using a von Frey test over a period of 30 days. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-immunized animals have significantly decreased withdrawal threshold, indicating the development of neuropathic pain-like symptoms. (B) Clinical scores were evaluated daily to assess paresis until DPI 30. 50% of the EAE-immunized mice developed paresis. (C) Ataxia was measured using a composite scoring system, and non-PTX EAE immunization led to ataxia development. Data is presented as mean ± SEM, ****p < 0.0001. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.0. Normality tests determined the use of appropriate statistical analyses. von Frey and ataxia data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (α = 0.05) with model as the between-subjects factor and time as the repeated measure. Paresis severity was evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC) across all measurement days, with significance assessed by an unpaired t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Validation of protocol

This protocol has also been utilized and validated in prior studies showing that non-PTX EAE immunization not only induces neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation but also reproduces the sex-specific characteristics of multiple sclerosis:

Gupta et al. [30]. Sex-chromosome complement and Activin-A shape the therapeutic potential of TNFR2 activation in a model of MS and CNP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426771122.

Gupta et al. [29]. Investigating mechanisms underlying the development of paralysis symptom in a model of MS. Brain Res Bull. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2025.111275 (For pathology, please refer to Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Nguyen et al. [31]. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 activation elicits sex-specific effects on cortical myelin proteins and functional recovery in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Res Bull. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2024.110885.

Murphy et al. [27]. Synaptic alterations and immune response are sexually dimorphic in a non-pertussis toxin model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113061. (For sex differences, please refer to Figure 1A, B, Figure 5, Figure 6, and Figure 7)

Fischer et al. [28]. Exogenous activation of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 promotes recovery from sensory and motor disease in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.021.

General notes and troubleshooting

General notes

1. The M. tuberculosis used in this study is heat-inactivated and therefore noninfectious. Nevertheless, because heat-killed preparations can still pose inhalation or irritation risks before emulsification, they should be handled under a standard laboratory chemical fume hood until fully mixed with CFA.

2. To ensure complete immune activation, do not change the cage the day of and three days after the immunization.

3. Animals need to be under minimal stress; therefore, avoid any animal handling for 48 h unless necessary.

4. Monitor the weight of the animals as it indicates health status and the probability of developing paresis.

5. When paresis develops, provide food pellets directly onto the bedding and provide diet gels.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Animals exhibit neuropathic pain–like behaviors without developing paresis.

Possible causes: Incomplete or inadequate delivery of MOG emulsion due to improper injection depth or tissue compartment targeting.

Solution: Confirm that the MOG emulsion is delivered strictly subcutaneously. Inadvertent intramuscular injection can prevent proper emulsion dispersion and antigen presentation. Re-evaluate injection technique and needle angle to ensure consistent subcutaneous placement.

Problem 2: Excessive resistance when depressing the syringe plunger during emulsion injection into animals.

Cause: Introduction of air bubbles during transfer of the MOG emulsion from the 10-mL preparation syringe into the 1-mL dosing syringe, resulting in back-pressure and impaired flow.

Solution: Carry additional sterile 1-mL syringes with needles in advance when going for animal injections. If high plunger resistance occurs, remove the needle from the problematic syringe and transfer the emulsion into a new 1-mL syringe with its plunger removed, minimizing further air introduction. Reinsert the plunger into the new syringe, attach a fresh needle, and proceed with injection.

Supplementary information

The following supporting information can be downloaded here:

1. Figure S1. Mortar and pestle.

2. Figure S2. Modified syringe.

3. Figure S3. Modified syringe with parafilm.

4. Figure S4. Emulsion.

5. Figure S5. Emulsion transfer to the 1-mL syringe.

6. Figure S6. A 1-mL syringe with plunger insertion.

7. Figure S7. Marked site for subcutaneous injection.

Acknowledgments

Conceptualization, K.L.N., S.G.; Investigation, K.L.N., S.G., S.A., E.S.; Writing—Original Draft, S.G., S.A.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.G., K.L.N.; Supervision, K.L.N., S.G.

The following figures were created using BioRender: Graphical overview, Nguyen, K. (2026), https://BioRender.com/h48d938.

The authors acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS124123, NINDS) and departmental funds from the George Washington University Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology awarded to Dr. John R. Bethea. We also thank Dr. Bethea for his supervision and continued support during the development of this protocol and associated manuscripts.

This protocol was used in [27,29,30,31].

Competing interests

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Walton, C., King, R., Rechtman, L., Kaye, W., Leray, E., Marrie, R. A., Robertson, N., La Rocca, N., Uitdehaag, B., van der Mei, I., et al. (2020). Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler. 26(14): 1816–1821. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520970841

- Lim, S. Y. and Constantinescu, C. S. (2010). Current and future disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis. Int J Clin Pract. 64(5): 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02261.x

- Rejdak, K., Jackson, S. and Giovannoni, G. (2010). Multiple sclerosis: a practical overview for clinicians. Br Med Bull. 95(1): 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldq017

- Yiu, E. M. and Banwell, B. (2010). Update on emerging therapies for multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 10(8): 1259–1262. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.10.98

- Krishnamoorthy, G. and Wekerle, H. (2009). EAE: An immunologist's magic eye. Eur J Immunol. 39(8): 2031–2035. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200939568

- Constantinescu, C. S., Farooqi, N., O'Brien, K. and Gran, B. (2011). Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a model for multiple sclerosis (MS). Br J Pharmacol. 164(4): 1079–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01302.x

- Giralt, M., Molinero, A. and Hidalgo, J. (2018). Active Induction of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) with MOG35–55 in the Mouse. Methods Mol Biol. 1791: 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7862-5_17

- Glatigny, S. and Bettelli, E. (2018). Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) as Animal Models of Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 8(11): a028977. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a028977

- Rangachari, M. and Kuchroo, V. K. (2013). Using EAE to better understand principles of immune function and autoimmune pathology. J Autoimmun. 45: 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2013.06.008

- Robinson, A. P., Harp, C. T., Noronha, A. and Miller, S. D. (2014). The experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS. Handb Clin Neurol. 122: 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-52001-2.00008-x

- Voskuhl, R. R. and MacKenzie-Graham, A. (2022). Chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is an excellent model to study neuroaxonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci. 15: e1024058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.1024058

- Hamilton, A. M., Forkert, N. D., Yang, R., Wu, Y., Rogers, J. A., Yong, V. W. and Dunn, J. F. (2019). Central nervous system targeted autoimmunity causes regional atrophy: a 9.4T MRI study of the EAE mouse model of Multiple Sclerosis. Sci Rep. 9(1): 8488. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44682-6

- O'connor, K. C., Bar-Or, A. and Hafler, D. A. (2001). The Neuroimmunology of Multiple Sclerosis: Possible Roles of T and B Lymphocytes in Immunopathogenesis. J ClinImmunol. 21(2): 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011064007686

- Williams, K. L. and Brauer, S. G. (2022). Walking impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis: The impact of complex motor and non-motor symptoms across the disability spectrum. Aust J Gen Pract. 51(4): 215–219. https://doi.org/10.31128/ajgp-08-21-6116

- Lee, J. M., Dunn, J.(2013). Mobility Concerns in Multiple Sclerosis—Studies and Surveys on US Patient Populations of Relevance to Nurses. US Neurol. 9(1): 17. https://doi.org/10.17925/usn.2013.09.01.17

- Bittner, S., Afzali, A. M., Wiendl, H. and Meuth, S. G. (2014). Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG35-55) Induced Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE) in C57BL/6 Mice. J Visualized Exp.: e3791/51275. https://doi.org/10.3791/51275

- Kügler, S., Böcker, K., Heusipp, G., Greune, L., Kim, K. S. and Schmidt, M. A. (2007). Pertussis toxin transiently affects barrier integrity, organelle organization and transmigration of monocytes in a human brain microvascular endothelial cell barrier model. Cell Microbiol. 9(3): 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00813.x

- Kerfoot, S. M., Long, E. M., Hickey, M. J., Andonegui, G., Lapointe, B. M., Zanardo, R. C. O., Bonder, C., James, W. G., Robbins, S. M., Kubes, P., et al. (2004). TLR4 Contributes to Disease-Inducing Mechanisms Resulting in Central Nervous System Autoimmune Disease. J Immunol. 173(11): 7070–7077. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.7070

- Fields, T. A. and Casey, P. J. (1997). Signalling functions and biochemical properties of pertussis toxin-resistant G-proteins. Biochem J. 321(3): 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3210561

- Su, S. B., Silver, P. B., Zhang, M., Chan, C. C. and Caspi, R. R. (2001). Pertussis Toxin Inhibits Induction of Tissue-Specific Autoimmune Disease by Disrupting G Protein-Coupled Signals. J Immunol. 167(1): 250–256. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.250

- Mangmool, S. and Kurose, H. (2011). Gi/o Protein-Dependent and -Independent Actions of Pertussis Toxin (PTX). Toxins (Basel). 3(7): 884–899. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins3070884

- Alfano, M., Schmidtmayerova, H., Amella, C. A., Pushkarsky, T. and Bukrinsky, M. (1999). The B-Oligomer of Pertussis Toxin Deactivates Cc Chemokine Receptor 5 and Blocks Entry of M-Tropic HIV-1 Strains. J Exp Med. 190(5): 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.190.5.597

- Ronchi, F., Basso, C., Preite, S., Reboldi, A., Baumjohann, D., Perlini, L., Lanzavecchia, A. and Sallusto, F. (2016). Experimental priming of encephalitogenic Th1/Th17 cells requires pertussis toxin-driven IL-1β production by myeloid cells. Nat Commun. 7(1): e1038/ncomms11541. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11541

- Dumas, A., Amiable, N., de Rivero Vaccari, J. P., Chae, J. J., Keane, R. W., Lacroix, S. and Vallières, L. (2014). The Inflammasome Pyrin Contributes to Pertussis Toxin-Induced IL-1β Synthesis, Neutrophil Intravascular Crawling and Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. PLoS Pathog. 10(5): e1004150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004150

- Cassan, C., Piaggio, E., Zappulla, J. P., Mars, L. T., Couturier, N., Bucciarelli, F., Desbois, S., Bauer, J., Gonzalez-Dunia, D., Liblau, R. S., et al. (2006). Pertussis Toxin Reduces the Number of Splenic Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 177(3): 1552–1560. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1552

- Hofstetter, H. H., Shive, C. L. and Forsthuber, T. G. (2002). Pertussis Toxin Modulates the Immune Response to Neuroantigens Injected in Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant: Induction of Th1 Cells and Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in the Presence of High Frequencies of Th2 Cells. J Immunol. 169(1): 117–125. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.117

- Murphy, K. L., Fischer, R., Swanson, K. A., Bhatt, I. J., Oakley, L., Smeyne, R., Bracchi-Ricard, V. and Bethea, J. R. (2020). Synaptic alterations and immune response are sexually dimorphic in a non-pertussis toxin model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol. 323: 113061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113061

- Fischer, R., Padutsch, T., Bracchi-Ricard, V., Murphy, K. L., Martinez, G., Delguercio, N., Elmer, N., Sendetski, M., Diem, R., Eisel, U. L., et al. (2019). Exogenous activation of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 promotes recovery from sensory and motor disease in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 81: 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.021

- Gupta, S., Arnab, S., Silver-Beck, N., Nguyen, K. L. and Bethea, J. R. (2025). Investigating mechanisms underlying the development of paralysis symptom in a model of MS. Brain Res Bull. 223: 111275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2025.111275

- Gupta, S., Arnab, S., Nguyen, K. L., Reed, M., Fathi, P., Tammen, K., Turner, E., Jones, E., Fischer, R., Mendelowitz, D., et al. (2025). Sex-chromosome complement and Activin-A shape the therapeutic potential of TNFR2 activation in a model of MS and CNP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 122(20): e2426771122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2426771122

- Nguyen, K. L., Bhatt, I. J., Gupta, S., Showkat, N., Swanson, K. A., Fischer, R., Kontermann, R. E., Pfizenmaier, K., Bracchi-Ricard, V., Bethea, J. R., et al. (2024). Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 activation elicits sex-specific effects on cortical myelin proteins and functional recovery in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Res Bull. 207: 110885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2024.110885

Article Information

Publication history

Received: Oct 23, 2025

Accepted: Dec 23, 2025

Available online: Feb 2, 2026

Published: Feb 5, 2026

Copyright

© 2026 The Author(s); This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

How to cite

Gupta, S., Arnab, S., Stehle, E. and Nguyen, K. L. (2026). Advancing EAE Modeling: Establishment of a Non-Pertussis Immunization Protocol for Multiple Sclerosis. Bio-protocol 16(3): e5589. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5589.

Category

Immunology > Animal model > Mouse

Update

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link