- Submit a Protocol

- Receive Our Alerts

- Log in

- /

- Sign up

- My Bio Page

- Edit My Profile

- Change Password

- Log Out

- EN

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Home

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

Simple and Rapid Model to Generate Differentiated Endometrial Floating Organoids

Published: Vol 16, Iss 3, Feb 5, 2026 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5584 Views: 144

Reviewed by: Anonymous reviewer(s)

Protocol Collections

Comprehensive collections of detailed, peer-reviewed protocols focusing on specific topics

Related protocols

The Establishment of 3D Polarity-Reversed Organoids From Human Endometrial Tissue as a Model for Infection-Induced Endometritis

Xin Zhang [...] Zhaohui Liu

Jun 20, 2025 1761 Views

Protocol for 3D Bioprinting a Co-culture Skin Model Using a Natural Fibrin-Based Bioink as an Infection Model

Giselle Y. Díaz [...] Stephanie M. Willerth

Jul 20, 2025 3790 Views

A Simplified 3D-Plasma Culture Method for Generating Minimally Manipulated Autologous Equine Muscle-Derived Progenitor Cells

Hélène Graide [...] Didier Serteyn

Dec 5, 2025 1255 Views

Abstract

Nowadays, the use of 3D cultures (organoids) is considered a valuable experimental tool to model physiological and pathological conditions of organs and tissues. Organoids, retaining cellular heterogeneity with the presence of stem, progenitor, and differentiated cells, allow the faithful in vitro reproduction of structures resembling the original tissue. In this context, the growth of endometrial organoids allows the generation of 3D cultures characterized by a hollow lumen, secretory activity, and apicobasal polarity and displaying phenotypical modification in response to hormone stimulation. However, a limitation in currently used models is the absence of stromal cells in their structure; as a result, they miss epithelial–stromal interactions, which are crucial in endometrial physiology. We developed a novel 3D model to generate endometrial organoids grown in floating MatrigelTM droplets in the presence of standard culture medium. From a structural point of view, these novel floating 3D cultures develop as gland-like structures constituted by epithelial cells organized around a central lumen and retain the expression of endometrial and decidual genes, like previously published organoids, although with a phenotype resembling hormonally differentiated structures. Importantly, floating organoids retain stromal cells which grow in close contact with the epithelial cells, localized within the internal or external portion of the organoid structure. In summary, we present a simple and rapid model for generating 3D endometrial organoids that preserve epithelial–stromal cell interactions, promoting the formation of differentiated organoids and enabling the study of reciprocal modulation between epithelium and stroma.

Key features

• Development of 3D endometrial organoids using 10% FBS-DMEM/F12 complete medium in less than a month.

• Preservation of stromal and epithelial cell populations, favoring the study of their interaction.

• Development of differentiated endometrial organoids without the need for in vitro hormonal stimulation.

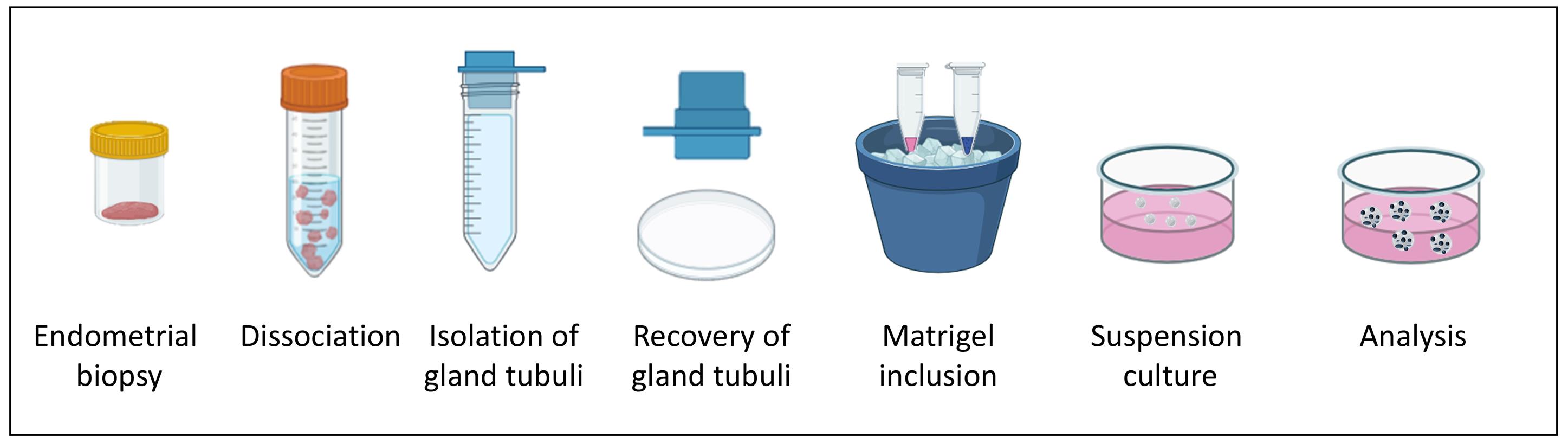

Keywords: Endometrial organoidsGraphical overview

Workflow of endometrial floating organoid formation

Background

Three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models represent a new frontier in biomedical research, dramatically changing the experimental approaches to tissue physiology and pathology. In particular, gland organoids are considered highly relevant in vitro models, since they can reconstitute the complex interactions among different cell types, which are at the basis of the tissue physiology and are often altered in pathological conditions.

In the past years, different types of epithelial organoids have been developed to study mechanisms determining reproductive tract diseases, providing an impressive advancement in modeling the reproductive system. Epithelial organoids have been established from many different regions of the female reproductive tract; among others, endometrial organoids represent nowadays a pillar in the study of endometrial dysfunctions and infertility [1]. In particular, endometrial organoids, reproducing endometrial architecture in vitro, provide an extremely valuable tool to model different physiological conditions and analyze tissue alterations occurring in pathology, as well as the efficacy of pharmacological treatments. In fact, they can recreate 3D structures from tissues derived from both healthy donors and endometrial-related disease patients.

Several different approaches have been used to develop organoid models able to reproduce endometrial complexity [2,3]. The endometrial tissue used to develop organoids can be obtained by laparoscopy or biopsy catheter, from all stages of the menstrual cycle, from the decidua, atrophic tissues, or menstrual blood [4–7], and from both fresh and cryopreserved samples [8]. Several types of pathological tissues (e.g., carcinomas, endometriotic lesions, or biopsies from infertile women) can also easily generate organoids, thus representing novel models to study endometrial physiology and pathology in different biological conditions, including all the phases of the implantation process [4,5,9].

Two seminal reports were published in 2017, in which the generation of endometrial gland organoids was described [5,7]. Organoids in both studies were generated starting from the in vitro growth of isolated glandular fragments, which were then embedded in an artificial extracellular matrix (i.e., MatrigelTM) in chemically defined culture media. 3D cultures displayed a genetically stable phenotype and self-renewing and self-organizing abilities, preserved responsiveness to hormone exposure, and exhibited cellular differentiation upon specific hormonal stimulation. Published endometrial organoids are organized as a single columnar epithelium with a central lumen, and are suitable for long-term cultures when grown in the presence of activators of Wnt and ERK1/2 signaling and inhibited TGFβ and BMP pathways [10,11].

Although endometrial gland organoids recapitulate the features of uterine glands, preserving spontaneously organized in vitro luminal and glandular elements, they cannot reproduce the midluteal endometrium, since they lack stromal and immune cell components and are devoid of vascular elements. This limits the information obtained on epithelial–stromal interactions, and thus their suitability for many highly specific analyses in which all these cell populations play a significant role.

To overcome these issues (mainly the lack of stromal cells within the 3D culture), more complex culture models have been developed and named assembloids. These were established by incorporating stromal cells with endometrial glandular organoids after their generation [3,12]. However, this approach is technically and experimentally challenging, namely regarding the introduction of a luminal epithelium and/or uterine natural killer cells and the development of protocols for long-term maintenance and propagation. A more advanced model of assembloids has been reported, in which endometrial epithelial and stromal cells were cultured using a matrix and air–liquid interface [13]. This model seems to better recapitulate endometrium anatomy, different cell population composition, and hormone-induced changes along the endometrial menstrual cycle. However, this model is technically challenging and difficult to develop.

In this scenario, we report a novel, simple, and cost-effective endometrial organoid model based on floating MatrigelTM droplets, which allows the formation of organoids containing both epithelial and stromal cellular components.

Starting from glandular elements isolated from fresh or cryopreserved Pipelle biopsies from women who underwent assisted reproductive technologies, we generated free-floating MatrigelTM organoids grown in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-DMEM/F12, which we named “floating organoids,” self-organized as round or elongated structures, formed by epithelial cells integrated with stromal cells around a central lumen. Floating organoids were obtained from 100% of the biopsies analyzed [14], demonstrating a high reproducibility even with very small amounts of starting tissue or when it is derived from patients.

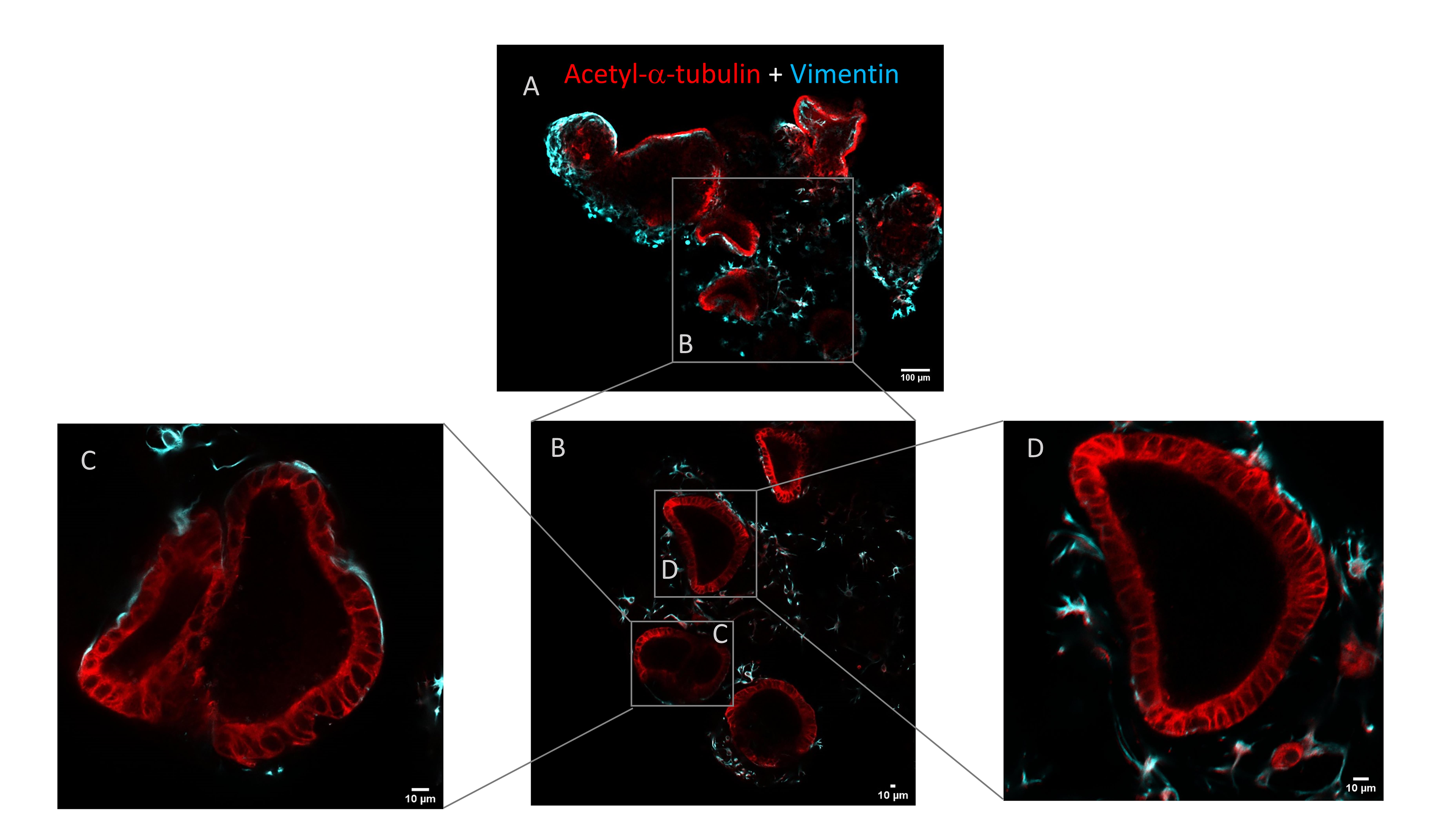

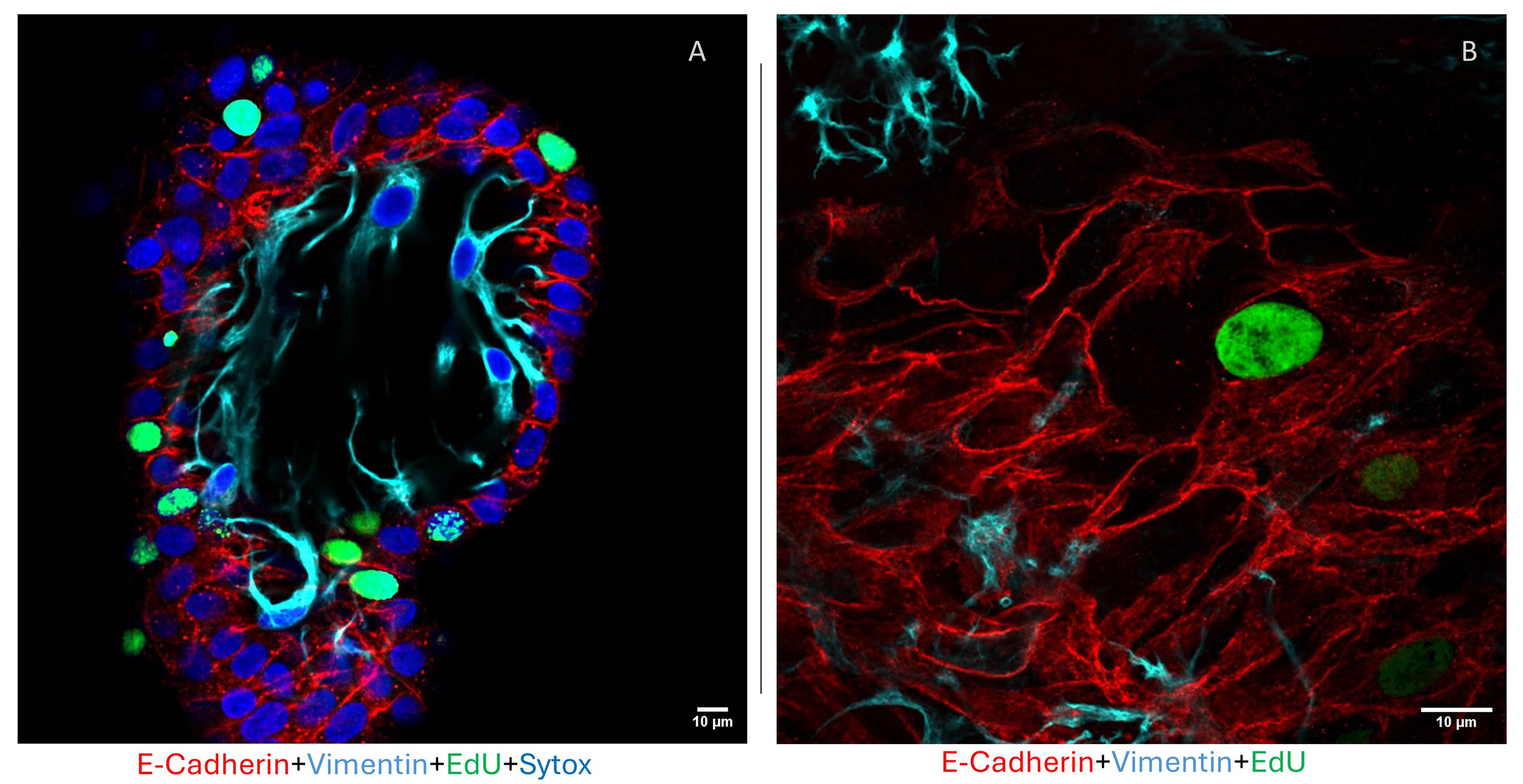

The comparison of this novel model with conventional organoids evidenced a morphology similar to the conventional organoid, being formed by a monolayer of epithelial cells organized as round or elongated sprouted structures surrounding an empty cavity. As observed in conventional organoids, floating organoids express E-cadherin, mucin 1, and acetyl-α-tubulin, confirmed by the epithelial origin of the cells composing the glandular structure. A significant presence of vimentin-expressing stromal cells, mostly localized in close contact with epithelial cells, was detected in floating but not in conventional organoids.

In our simplified model, we propose the use of conventional medium supplemented only with FBS, representing an easy and inexpensive way to obtain 3D cultures. Compared to the use of chemically defined media, FBS provides a more suitable environment for the growth of stromal cells, which is prevented in conventional organoid cultures by a medium that may actually counteract stromal cell growth and persistence in the 3D structure. Moreover, the floating culture growth also prevents stromal cells from the organoids from growing on the plastic interface of the Petri dish, consequently favoring their integration with the endometrial epithelium. This is a particularly relevant difference between the two types of 3D cultures, since the reduced presence of stroma cells represents a major limitation of conventional organoids, as the interaction between epithelial and stromal cells plays a central role in hormonal differentiation. In fact, the persistent presence of stromal cells promotes cell differentiation, as assessed for decidualization marker expression, making floating organoids a valuable model of differentiated organoids. On the other hand, the differentiation of floating spheroids in serum-supplemented medium, without the necessity of hormonal differentiation, leads to a reduction in stemness, and the differentiation status reduces the possibility of prolonged in vitro propagation, being limited to one or two passages.

In conclusion, here we describe a simple and rapid protocol to generate differentiated endometrial organoids, which retain both epithelial and stromal cells in the 3D structure. The interaction between these cell populations may allow the study of their reciprocal modulation, in particular during the differentiation process.

Materials and reagents

Biological materials

1. Human endometrial tissues (0.5 × 1.0 cm) (generated in patients who underwent assisted reproductive technologies at the Reproductive Medicine Unit, Gynecology and Obstetrics Department of the International Evangelical Hospital, Genova, Italy); samples were collected during the secretory phase of the cycle, without hormonal stimulation, with a Pipelle catheter.

Reagents

1. Collagenase Type V (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: C9263-100MG)

2. Dispase II (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: D4693-1G)

3. DMEM/F12 (Euroclone, catalog number: ECM0095L)

4. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, catalog number: 10270106)

5. DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: DN25-100MG)

6. PBS 1× (Euroclone, catalog number: ECB4004L)

7. Antibiotics Pen/Strep 100× (Euroclone, catalog number: ECB 3001D)

8. L-Glutamine 200 mM (Euroclone, catalog number: ECB3000D)

9. Ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS number: 64-17-5)

10. Parafilm (AMCOR, catalog number: PM-996)

11. MatrigelTM growth factor reduced (GFR) (Corning, catalog number: 354230)

12. 16% formaldehyde solution (Thermo Scientific, catalog number: 28908)

13. 0.1 M glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS number: 56-40-6)

14. Normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: G9023)

15. Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS number, 9036-19-5)

16. Rabbit anti-vimentin (EPR3776) antibody (Abcam, catalog number: ab92547)

17. Mouse anti-cadherin (HECD-1) antibody (Abcam, catalog number: ab1416)

18. Mouse anti-acetyl-α-tubulin (Lys40) (6-11B-1) antibody (Cell Signaling, catalog number: 12152)

19. Goat anti-mouse IgG (H-L) Alexa FluorTM 568 antibody (Invitrogen, catalog number: A-11004)

20. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa FluorTM 647 antibody (Invitrogen, catalog number: A21245)

21. Sytox Blue nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen, catalog number: S11348)

22. Cell recovery solution (Corning, catalog number: 354253)

23. Aurum Total RNA mini kit (Bio-Rad, catalog number: 7326820)

24. Sodium acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS number, 127-09-3)

25. Calcium acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS number, 62-54-4)

26. Edu DetectPro Cell Proliferation Imaging kit (Baseclick GmbH, catalog number BCK-EduPro-IM488)

Solutions

1. Collagenase V stock solution 100× (see Recipes)

2. Dispase II stock solution 40× (see Recipes)

3. DNase I stock solution 100× (see Recipes)

4. DMEM/F12 basal medium (see Recipes)

5. 10% FBS-DMEM/F12 complete medium (see Recipes)

6. Enzyme digestion solution (see Recipes)

7. 4% Formaldehyde stock solution (see Recipes)

8. 1% Formaldehyde working solution (see Recipes)

9. Blocking-permeabilizing solution 1× (see Recipes)

Recipes

1. Collagenase V stock solution 100×

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase V | 40 mg/mL | 100 mg |

| PBS w/o Ca2+ and Mg2+ | 1× | to 2.5 mL |

| Total | - | 2.5 mL |

Dissolve 100 mg of collagenase type V powder in 2.5 mL of PBS w/o Ca2+ and Mg2+ and sterilize through a 0.22 μm filter. Store aliquots at -20 °C.

2. Dispase II stock solution 40×

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| Dispase II | 50 U/mL | 1 g |

| 10 mM NaAc pH 7.5 and 5 mM CaAc | - | to 10 mL |

| Total | - | 10 mL |

Prepare a 20 mL solution of 10 mM NaAc (pH 7.5) with 5 mM CaAc and sterilize by filtration with a 0.22 μm filter. Dissolve 1 g of Dispase II in 10 mL of the filtered NaAc + CaAc solution.

3. DNase I stock solution 100×

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I | 40 mg/mL | 100 mg |

| H2O | - | to 2.5 mL |

| Total | - | 2.5 mL |

4. DMEM/F12 basal medium

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 | 1× | 490 mL |

| L-Glutamine | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Pen/Strep | Pen 100 U/mL; Strep 0.1 mg/mL | 5 mL |

| Total | - | 500 mL |

5. 10% FBS-DMEM/F12 complete medium

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 basal medium | 1× | 450 mL |

| FBS | 10% | 50 mL |

| Total | - | 500 mL |

6. Enzyme digestion solution

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| 10%FBS-DMEM/F12complete medium | 1× | 3,820 mL |

| Collagenase V 100× | 0.4 mg/mL | 40 μL |

| Dispase 40× | 1.25 U/mL | 100 μL |

| DNase 100× | 0.4 mg/mL | 40 μL |

| Total | - | 4 mL |

7. 4% formaldehyde stock solution

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| 16% formaldehyde solution | 4% | 10 mL |

| PBS 1× | - | 30 mL |

| Total | - | 40 mL |

8. 1% formaldehyde working solution

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| 4% formaldehyde solution | 1% | 2.5 mL |

| PBS 1× | - | 7.5 mL |

| Total | - | 10 mL |

9. Blocking-permeabilizing solution 1×

| Reagent | Final concentration | Quantity or volume |

|---|---|---|

| Normal goat serum | 10% | 0.5 mL |

| 1% Triton X-100 | 0.1% | 0.5 mL |

| PBS 1× | - | 4 mL |

| Total | - | 5 mL |

Laboratory supplies

1. 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf, catalog number: 0030120086)

2. 15 and 50 mL conical tubes (Euroclone, catalog numbers: ET5015B, ET5050B)

3. 5 and 10 mL sterile pipettes (Euroclone, catalog numbers: EPS05N, EPS10N)

4. 10, 200, and 1,000 μL sterile tips (Euroclone, catalog numbers: ECTD00010, ECTD00200, ECTD01005)

5. 100 μm cell sieves (100 μm cell strainer) (Corning, catalog number: 431752)

6. 35, 60, and 100 mm Petri dishes (Euroclone, catalog numbers: ET2035, ET2060, ET2100)

7. Disposable stainless steel blade scalpels No. 23 (GIMA, catalog number: 27067)

8. Sterile tweezers

9. 3 mL plastic Pasteur pipette (Copan, catalog number: 200)

10. Empty 96-well rack of 10 μL tips (Eppendorf ep Dualfilter T.I.P.S., catalog number: 0030078500)

11. Nunc non-treated multidish 4 wells (Thermo Scientific, catalog number: 179820)

Equipment

1. Refrigerator 2–8 °C (Liebherr, model: SRFvg 3501-20A-001)

2. Freezer -20 °C (Liebherr, model: GP 2733 Index 20D/001) and -80 °C (Forma Scientific, model: 925)

3. Water bath (GFL)

4. Biological safety cabinet (BioAir Top-Safe, model: 1.8)

5. Laboratory centrifuge with rotor for 10- and 50-mL conical tubes (Eppendorf, model: 5810 R)

6. Laboratory centrifuge with rotor for 1.5- and 2.0-mL tubes (Eppendorf, model: 5415 R)

7. Water jacketed CO2 incubator (Forma Scientific Instruments, model: 3111)

8. Automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, model: TC20)

9. Digital inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, model: DMIL) equipped with camera (Leica Microsystems, model: ICC50HD)

10. Confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, model: Stellaris 8 STED)

Procedure

A. Isolation of endometrial gland elements

1. Perform all procedures in a biosafety cabinet to preserve sterility.

2. Prepare Recipes 1, 2, and 3; sterilize all solutions by filtration through a 0.2 μm filter and store the aliquots at -20 °C.

3. Prepare a culture Petri dish (100 mm) with 10 mL of sterile PBS solution supplemented with 0.1 mL of 100× Pen/Strep (final concentration: penicillin 100 U/mL, streptomycin 0.1 mg/mL) to clean the endometrial tissue collected by Pipelle.

Note: Pipelle biopsies should preferably be processed on the day of collection. If immediate processing is not possible, store the sample at 4 °C to preserve vitality.

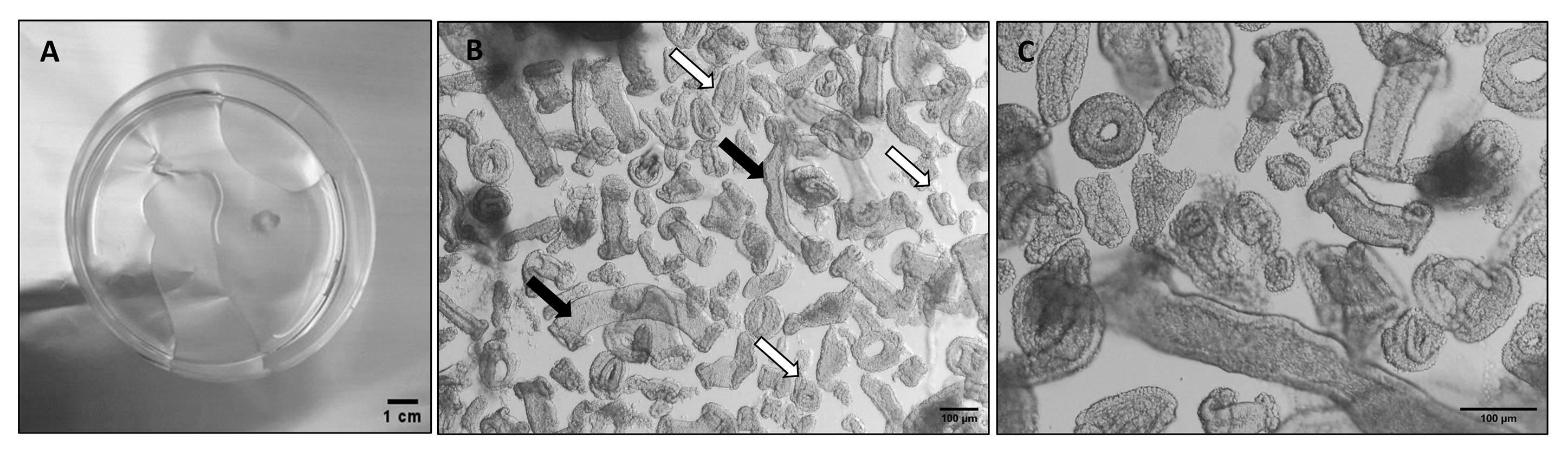

4. Transfer the sample tissue to the Petri dish and gently agitate to remove clots and debris (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Dissociation of an endometrial Pipelle biopsy. (A) Petri dish containing an endometrial Pipelle biopsy after cleaning (step A4). (B) Brightfield representative image of gland tubular elements after dissociation (step A11); white arrows mark the optimal size of the glandular fragments, and black arrows mark too-long glandular elements. (C) Magnification of gland elements.

5. Transfer the washed tissue into a new Petri dish containing 10% FBS-DMEM/F12 complete medium (see Recipe 5) and cut the tissue with a sterile steel blade scalpel into small fragments (0.1 × 0.1 cm).

6. Transfer the dissected tissue into a 50 mL sterile centrifuge tube.

7. Centrifuge at 146 rcf for 8 min.

8. Prepare enzyme digestion solution following Recipe 6. Recalibrate the volume of enzyme digestion in relation to the size of the biopsy (larger tissue fragments may require a larger digestion volume).

9. Carefully remove the supernatant without disturbing the tissue pellet using a pipette.

10. Add 4 mL of enzymatic digestion solution to the tissue pellet and incubate at 37 °C with gentle shaking to ensure uniform exposure of the tissue to the enzyme solution.

11. After 20 min, check that digestion has taken place by observing the presence of free glandular elements. Take up 20 μL of the sample, place it on a 35 mm Petri dish, and observe under the inverted microscope. Continue incubation at 10-min intervals until digestion is complete (Figure 1B).

Caution: The time of incubation is a critical step. Monitoring the digestion is necessary since the enzyme can cause cell death, but insufficient digestion limits the release of glandular elements.

12. Terminate incubation by diluting the sample with 4 mL of 10% FBS-DMEM/F12 complete medium to minimize further disaggregation.

13. Leave the tube to stand for 2 min to allow undigested fragments to sediment.

14. Filter the supernatant through a 100 μm cell sieve and wash with 5 mL of DMEM/F12 basal medium (see Recipe 4).

15. Invert the sieve over a 60 mm Petri dish and backwash the glandular elements from the membrane by strongly pipetting 5 mL of DMEM/F12 basal medium using a plastic Pasteur pipette. Transfer the backwashed glandular elements to a 15 mL tube and pellet by centrifuging at 500× g for 5 min.

16. Resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of DMEM/F12 basal medium and gently pipette up and down several times to partially dissociate the glands.

17. Test the gland fragmentation by observing a test droplet under the microscope; if long tubular fragments are still evident, continue to dissociate. In Figure 1B, the optimal (white arrow) dimensions of the gland fragments are indicated.

18. Transfer to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and pellet by centrifugation at 500× g for 8 min.

19. Remove the supernatant and estimate the volume of the pellet.

20. Flick the tube to loosen the pellet and place it on ice for 2–5 min.

B. Preparation of Parafilm mold

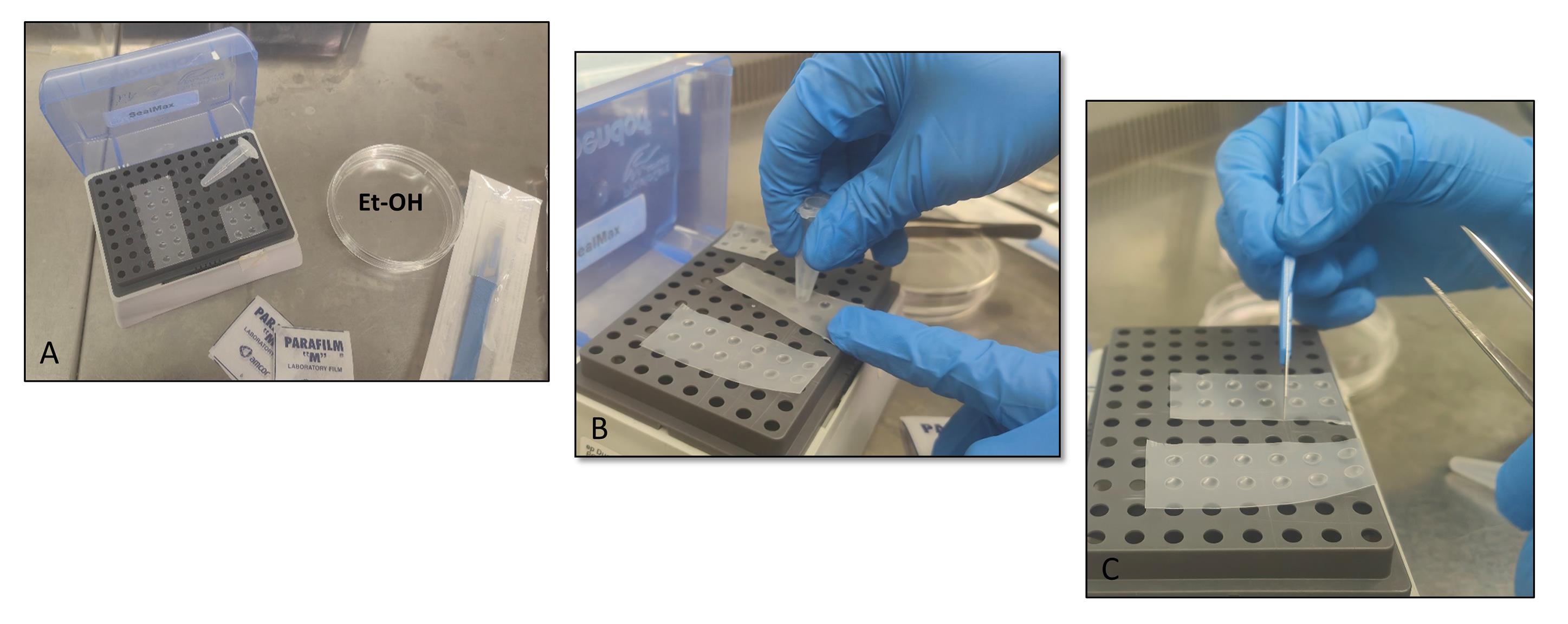

1. Cut 3 × 4 cm Parafilm strips and store them at -20 °C (low temperature increases parafilm stiffness, favoring the subsequent steps, but it is not required).

2. Place the Parafilm strip on the top of an empty rack of a 96-well box of 10 μL tips (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Preparation of the Parafilm mold. (A) Material needed to prepare the Parafilm molds. (B) Formation of round depressions on the Parafilm strip (steps B2–3). (C) Cutting of the Parafilm strip (step B4).

3. Press the Parafilm strip into the rack’s holes using the bottom of a 1.5 mL tube to create round depressions (Figure 2B).

4. Cut the Parafilm strip to obtain 2–4 depression spots (Figure 2C).

5. Sterilize the Parafilm strip by immersion in 100% ethanol for 30 min.

6. Dry the Parafilm strips by leaving them in a new Petri dish in a biosafety cabinet.

7. Use the Parafilm molds directly for the experiment or store them at 4 °C for further use.

C. Floating organoid seeding

1. Put a Parafilm strip into a sterile 60 mm Petri dish at room temperature.

2. Thaw a MatrigelTM aliquot at 4 °C and then put it on ice.

3. Resuspend the pellet (from step A18) in DMEM/F12 basal medium 1:1 (v/v) on ice (i.e., 20 μL of gland fragments + 20 μL of DMEM/F12 basal medium = 40 μL of suspension).

4. Mix the resuspended pellet with ice-cold MatrigelTM by adding 10× volume to the suspension (i.e., 40 μL of suspension + 360 μL MatrigelTM).

Notes:

1. This step is critical and not always standardizable. The size of the gland fragments may show differences between samples and can be affected by enzymatic digestion; moreover, the quantification and the resuspension of the pellet (step C3) are critical and sometimes difficult to estimate. It is recommended to place a test droplet (suspension/MatrigelTM) into a Petri dish and observe it under an inverted microscope to optimize sample concentration (Figure 3A).

2. If the tissue fragment concentration is too dense, further dilute the tissue sample with media and MatrigelTM in a 1:9 ratio. In our experience, we also diluted the sample only with DMEM/F12 basal medium, modifying the ratio of suspension/MatrigelTM and therefore the stiffness of droplets. The minimum ratio we tested was 20:80 of diluted sample to MatrigelTM. In any case, floating organoids also developed properly in a 1:4 ratio of sample to MatrigelTM.

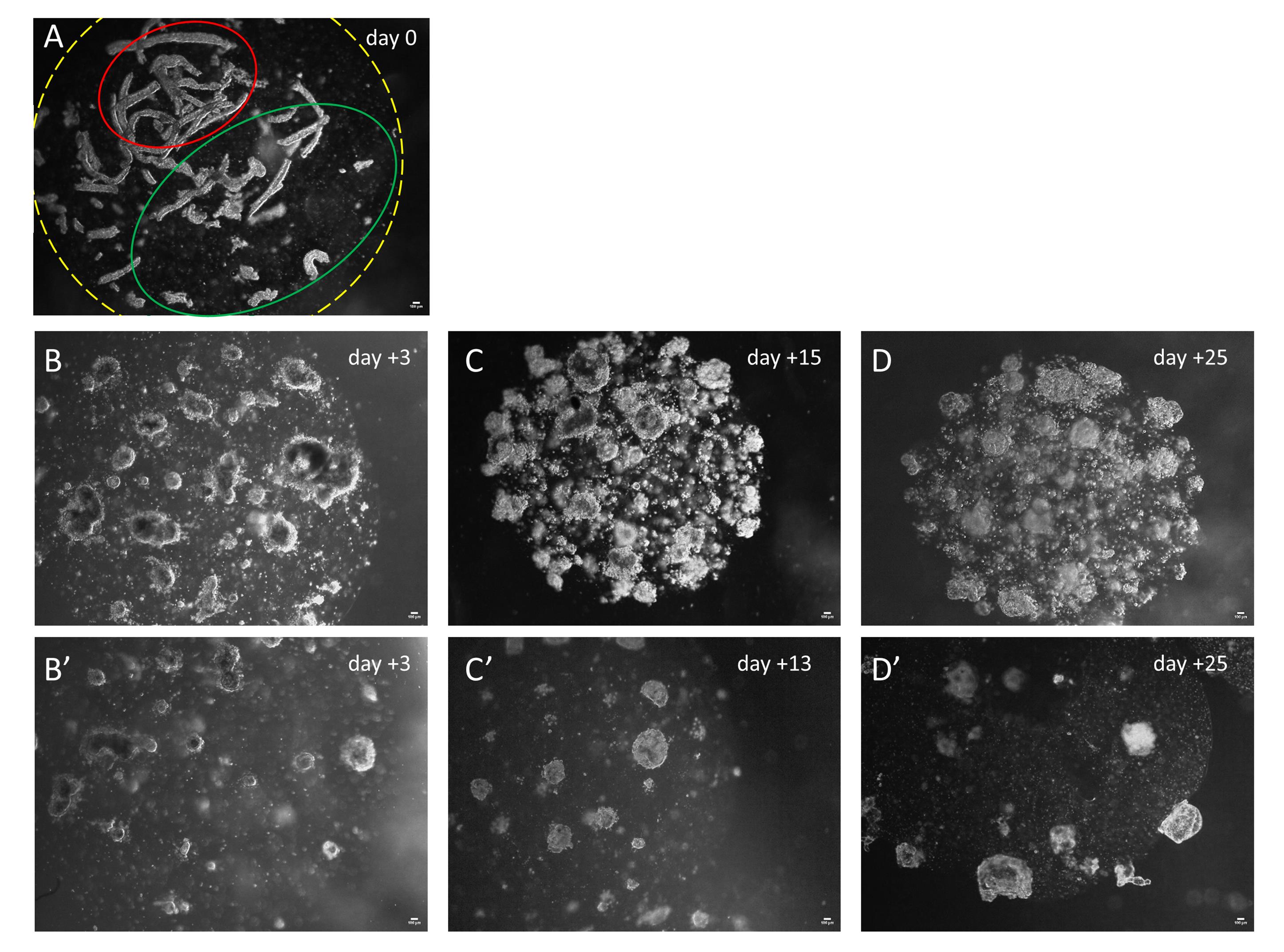

Figure 3. Floating organoid development in MatrigelTM droplets. (A) Representative MatrigelTM droplet within gland tubular fragments at the time of seeding (day 0). The yellow dotted line marks the edge of the droplet. The green line marks the optimal density of the glandular fragments into MatrigelTM droplets. The red line marks an area with an excessive density of glandular elements. (B–D) Representative images of floating organoids grown after 3 (B), 15 (C), and 25 (D) days of culture seeded at high gland fragment density. (B’–D’) Representative images of floating organoids originated by a culture seeded at low gland fragment density after 3 (B’), 13 (C’), and 25 (D’) days in vitro. Scale bars: 100 μm.

5. Dispense 30 μL of droplets of gland fragments (suspension)/MatrigelTM into each depression of the Parafilm mold, avoiding generating bubbles.

6. Incubate the plate at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 30 min.

7. Remove the MatrigelTM droplets from the Parafilm mold: using a 5 mL pipette, gently spurt 1–2 mL of 10% FBS DMEM/F12 complete medium sideways on the droplets.

8. Remove and throw away the Parafilm support and add 10 mL of 10% FBS DMEM/F12 complete medium per dish.

9. Check the floating droplets under a microscope and place the Petri dishes in the incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 (see Figure 3).

10. Change the medium every 3–4 days; carefully remove 8–9 mL of the old medium with a 5 mL pipette, making sure not to aspirate the floating droplets, and replace with the same volume of fresh 10% FBS DMEM/F12 complete medium.

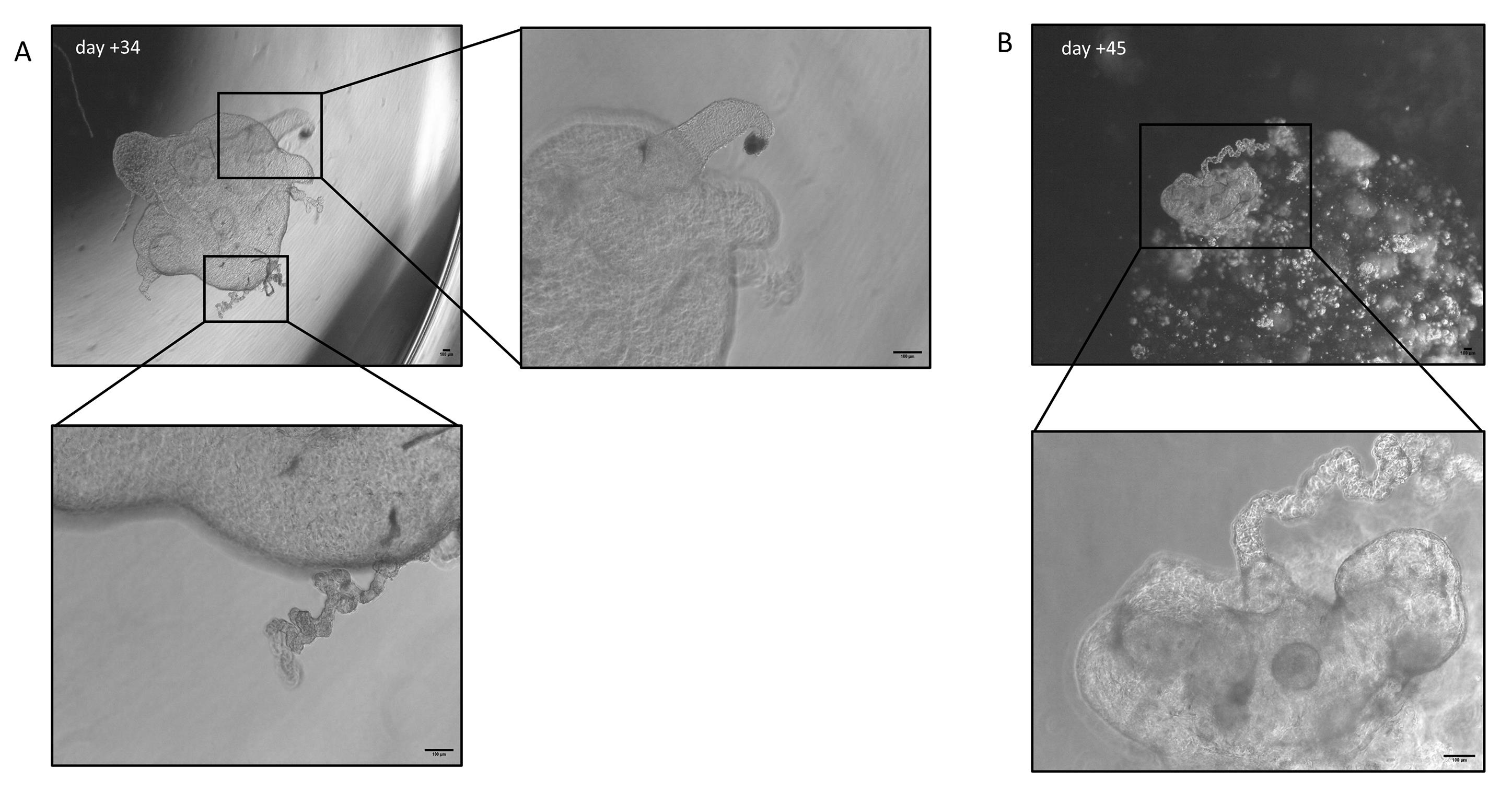

11. After 20–40 days in culture, organoids are mature enough for subsequent analysis (Figure 3D, D’ and Figure 4A, B).

Figure 4. Floating organoid development in MatrigelTM droplets. Representative images of floating organoids (low-density) grown for 34 (A) and 45 (B) days in culture; magnification of organoid structures delimited by the boxes. Scale bar: 100 μm.

D. Immunofluorescence of 3D floating organoids

1. Perform all procedures in a biosafety cabinet to preserve sterility.

2. Put 400 μL of PBS 1× per well of a new 4-well multidish.

3. Transfer floating organoids into a 4-well multidish, with one MatrigelTM droplet per well, using a plastic Pasteur pipette.

4. Wash floating organoids with PBS 1×.

Note: To wash floating organoids, use a 1 mL blue tip. Tilt the plate toward you and gently remove the media, always monitoring the movement of the organoid, which will move downward following the reduction of the liquid (like a fish in a pool). Discard the medium into a 2 mL tube; this way, you can eventually recover the sample accidentally sucked by the tip.

5. Fix with 1% formaldehyde solution (see Recipe 8) for 15 min.

6. Carefully remove formaldehyde solution.

7. Wash with PBS 1×.

Pause point: Fixed and unstained samples can be stored for months at 4 °C in sterile PBS. Ensure that the PBS does not evaporate too much; in case of long storage, rehydrate the sample.

8. Incubate with 200 μL of 0.1 M glycine for 10 min.

9. Remove glycine.

10. Add 200 μL of blocking-permeabilizing solution (see Recipe 9), at room temperature for at least 2.5 h.

11. Remove the blocking-permeabilizing solution.

12. Incubate overnight at 4 °C in 100 μL of blocking-permeabilizing solution with primary antibody [anti-vimentin (EPR3776), anti-cadherin (HECD-1), and anti-acetyl-α-tubulin (Lys40) (6-11B-1)] diluted 1/100. Tilt the dish by placing it on a support (i.e., the cap of a 50 mL tube).

13. Remove the solution and wash the floating organoids with PBS 1× for 15 min.

14. Repeat step D13 three times.

15. Incubate overnight at 4 °C in 100 μL of blocking-permeabilizing solution with the appropriate fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies (AF568 anti-mouse or AF647 anti-rabbit antibody) and Sytox nuclear dye, all diluted 1/200.

16. Remove the solution and wash the floating organoids with PBS 1× for 15 min.

17. Repeat step D16 three times.

18. Store your sample at 4 °C in PBS in a 4-well multidish sealed with Parafilm until analysis by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy.

Caution: Immunofluorescence staining is degraded by long storage. We recommend performing confocal acquisition within one week of sample staining.

E. Extraction of total RNA from floating organoids

1. Put 400 μL of PBS 1× per well of a new 4-well multidish.

2. Transfer floating organoids into a 4-well multidish, with one floating organoid per well, using a plastic Pasteur pipette.

3. Wash floating organoids with PBS 1×.

4. Transfer three floating organoids into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

5. Remove PBS 1× and add 250 μL of cell recovery solution and place on ice for 60 min.

6. Mix with pipette and spin at 600× g for 6 min at 4 °C.

7. Remove the medium and wash the pellet with 1 mL of PBS 1×.

8. Spin at 600× g for 6 min at 4 °C.

9. Add 350 μL of lysis buffer from the Aurum Total RNA mini kit.

10. Proceed with the RNA extraction following the kit instructions.

Note: RNA extraction yield is generally low; in our experience, by pulling three floating organoids, we obtained approximately 2.5 μg of mRNA.

Validation of protocol

The expression of both epithelial and stromal markers in floating organoids was established through immunofluorescence staining and qRT-PCR analysis.

Organoids developed into floating MatrigelTM droplets form round or elongated empty structures composed of monolayers of epithelial cells, integrated with stromal cells, distributed between or into the epithelial structures. This was demonstrated by the presence of cells expressing the epithelial markers acetyl-α-tubulin and E-cadherin and the stromal marker vimentin (Figures 5 and 6). For further immunofluorescence analysis, please refer to Figures 3 and 4, Videos, and Supplementary figures of [14].

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence staining of epithelial and stromal cells in floating organoids. (A) Whole-mount immunostaining for acetyl-α-tubulin (red) and vimentin (cyan) expression in floating organoids. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B–D) Magnifications of the selected zones delimited by the boxes. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Figure 6. Immunofluorescence staining of epithelial and stromal cells in floating organoids. (A) Whole-mount immunofluorescence representative image of a floating organoid pulsed overnight with 5-EdU stained for the epithelial marker E-cadherin (red), the stromal marker vimentin (cyan), the proliferative EdU-positive cells (green), and Sytox (blue) nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Magnification of stromal and epithelial interaction in a floating organoid. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Expression of endometrial and decidual genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR in comparison with conventional organoids before and after in vitro hormonal differentiation. Results support that endometrial organoids grown by following the protocol described here increase the differentiated gene expression profile (progesterone receptor, osteopontin, IGF1-binding protein 1, and FOXO1, among others). For detailed results of qRT-PCR experiments, please refer to Figures 6 and 7 and Supplementary figures of [14].

This protocol (or parts of it) has been used and validated in the following research article: Bajetto et al. (2025) Floating endometrial organoid model recapitulates epithelial-stromal cell interactions in vitro [14].

General notes and troubleshooting

General notes

1. MatrigelTM should always be handled on ice since it can degrade and solidify at room temperature. Thaw a MatrigelTM unopened bottle in an ice bucket stored overnight at 4 °C. Make single-use aliquots of MatrigelTM and store them at -20 °C.

2. Floating organoids are almost transparent, breakable structures. All steps must be performed carefully, always monitoring the number of organoids present in the Petri dishes. Do not use the vacuum pump, only pipette tips. Keeping a test tube for media changes and washes will be useful for recovering any accidentally aspirated sample. Place a black sheet or tray under the dishes to form a black background to improve organoid visibility.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Fixation with formaldehyde solution influences the MatrigelTM droplet solidity.

Possible cause: Formaldehyde solution and long-term culture damage the MatrigelTM structure, while organoids grown into the droplets strengthen the structure. After fixation, floating droplets can break into several units, each of which contains some organoids.

Solution: The broken units can be stained by immunofluorescence and included in paraffin or cryostat embedding medium. If the organoids are well developed, you can use 4% formaldehyde solution to fix them.

Problem 2: Concentration of gland fragments in the MatrigelTM droplet is too high.

Possible cause 1: Sample is not properly mixed with the MatrigelTM droplets.

Solution 1: Mix the tissue fragments several times with the MatrigelTM on ice. Avoid the formation of bubbles by using a pipette of a smaller volume than that of the sample.

Possible cause 2: Incorrect estimate of pellet volume.

Solution 2: Spot a test MatrigelTM/gland fragment droplet on a Petri dish and observe it under an inverted microscope. Optimize the sample concentration by adding medium and MatrigelTM to reach a suspension/MatrigelTM ratio of 1:9.

Problem 3: Restricted ability to sustain long-term in vitro propagation.

Possible cause: The acquisition of the differentiated status reduces the stemness and limits organoid propagation to one or two passages (when disassembled, they are no longer able to grow).

Solution: Gland fragments isolated from the biopsy can be cryo-stored for further experiments.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions: A.B., T.F.: Conceptualization. A.B., A.P., A.C., B.F.T., S.T., F.B.: Investigation. A.B., T.F.: Writing—Original Draft. All authors: Writing—Review & Editing. A.B., T.F.: Supervision.

The authors are grateful to all women who donated tissue for research, to Monica Gatti, Valerio Pisaturo, Denise Colia, Elena Pastine, and Mauro Costa, International Evangelical Hospital (Genova, Italy) for providing Pipelle biopsies, and to Dr. E. Gatta and DIFILAB laboratory (Univ. of Genova) for the Leica Stellaris 8 STED confocal microscope use.

The protocol described here was based on the previous original research paper: Bajetto et al. (2025), Exp Cell Res. 452(1): 114749. Doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2025.114749 [14].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical considerations

All tissue samples used in this study were obtained with written informed consent from all participants, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000 and with institutional Liguria Ethical Committee approval (approval n° P.R. 406REG2017).

References

- Alzamil, L., Nikolakopoulou, K. and Turco, M. Y. (2021). Organoid systems to study the human female reproductive tract and pregnancy. Cell Death Differ. 28(1): 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-0565-5

- Liu, Y., Sun, Y. and Cheng, S. (2024). Advances in the use of organoids in endometrial diseases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 166(2): 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15422

- Rawlings, T. M., Makwana, K., Tryfonos, M. and Lucas, E. S. (2021). Organoids to model the endometrium: implantation and beyond. Reprod Fertil. 2(3): R85–R101. https://doi.org/10.1530/raf-21-0023

- Boretto, M., Maenhoudt, N., Luo, X., Hennes, A., Boeckx, B., Bui, B., Heremans, R., Perneel, L., Kobayashi, H., Van Zundert, I., et al. (2019). Patient-derived organoids from endometrial disease capture clinical heterogeneity and are amenable to drug screening. Nat Cell Biol. 21(8): 1041–1051. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-019-0360-z

- Turco, M. Y., Gardner, L., Hughes, J., Cindrova-Davies, T., Gomez, M. J., Farrell, L., Hollinshead, M., Marsh, S. G. E., Brosens, J. J., Critchley, H. O., et al. (2017). Long-term, hormone-responsive organoid cultures of human endometrium in a chemically defined medium. Nat Cell Biol. 19(5): 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3516

- Cindrova-Davies, T., Zhao, X., Elder, K., Jones, C. J. P., Moffett, A., Burton, G. J. and Turco, M. Y. (2021). Menstrual flow as a non-invasive source of endometrial organoids. Commun Biol. 4(1): 651. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02194-y

- Boretto, M., Cox, B., Noben, M., Hendriks, N., Fassbender, A., Roose, H., Amant, F., Timmerman, D., Tomassetti, C., Vanhie, A., et al. (2017). Development of organoids from mouse and human endometrium showing endometrial epithelium physiology and long-term expandability. Development. 144(10): 1775–1786. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.148478

- Bui, B. N., Boretto, M., Kobayashi, H., van Hoesel, M., Steba, G. S., van Hoogenhuijze, N., Broekmans, F. J., Vankelecom, H. and Torrance, H. L. (2020). Organoids can be established reliably from cryopreserved biopsy catheter-derived endometrial tissue of infertile women. Reprod Biomed Online. 41(3): 465–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.03.019

- Zhou, W., Barton, S., Cui, J., Santos, L. L., Yang, G., Stern, C., Kieu, V., Teh, W. T., Ang, C., Lucky, T., et al. (2022). Infertile human endometrial organoid apical protein secretions are dysregulated and impair trophoblast progenitor cell adhesion. Front Endocrinol. 13: e1067648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1067648

- Nikolakopoulou, K. and Turco, M. Y. (2021). Investigation of infertility using endometrial organoids. Reproduction. 161(5): R113–R127. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-20-0428

- Lou, L., Kong, S., Sun, Y., Zhang, Z. and Wang, H. (2022). Human Endometrial Organoids: Recent Research Progress and Potential Applications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10: e844623. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.844623

- Rawlings, T. M., Makwana, K., Taylor, D. M., Molè, M. A., Fishwick, K. J., Tryfonos, M., Odendaal, J., Hawkes, A., Zernicka-Goetz, M., Hartshorne, G. M., et al. (2021). Modelling the impact of decidual senescence on embryo implantation in human endometrial assembloids. eLife. 10: e69603. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.69603

- Tian, J., Yang, J., Chen, T., Yin, Y., Li, N., Li, Y., Luo, X., Dong, E., Tan, H., Ma, Y., et al. (2023). Generation of Human Endometrial Assembloids with a Luminal Epithelium using Air–Liquid Interface Culture Methods. Adv Sci. 10(30): e202301868. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202301868

- Bajetto, A., Pattarozzi, A., Corsaro, A., Tremonti, B., Gatti, M., Pisaturo, V., Campagnolo, L., Colia, D., Pastine, E., Alteri, A., et al. (2025). A floating endometrial organoid model recapitulates epithelial-stromal cell interactions in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 452(1): 114749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2025.114749

Article Information

Publication history

Received: Nov 3, 2025

Accepted: Dec 17, 2025

Available online: Jan 7, 2026

Published: Feb 5, 2026

Copyright

© 2026 The Author(s); This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

How to cite

Bajetto, A., Pattarozzi, A., Corsaro, A., Tremonti, B. F., Thellung, S., Barbieri, F. and Florio, T. (2026). Simple and Rapid Model to Generate Differentiated Endometrial Floating Organoids. Bio-protocol 16(3): e5584. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5584.

Category

Stem Cell > Organoid culture

Cell Biology > Cell isolation and culture > 3D cell culture

Developmental Biology > Cell growth and fate > Differentiation

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link