- Submit a Protocol

- Receive Our Alerts

- Log in

- /

- Sign up

- My Bio Page

- Edit My Profile

- Change Password

- Log Out

- EN

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

- EN - English

- CN - 中文

- Home

- Protocols

- Articles and Issues

- For Authors

- About

- Become a Reviewer

Simple Methods for Permanent or Transient Denervation in Mouse Sciatic Nerve Injury Models

(*contributed equally to this work) Published: Vol 12, Iss 11, Jun 5, 2022 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.4430 Views: 4097

Reviewed by: Chiara AmbrogioJohn W PetersonMaría Delgado Esteban

Protocol Collections

Comprehensive collections of detailed, peer-reviewed protocols focusing on specific topics

Related protocols

Myonecrosis Induction by Intramuscular Injection of CTX

Simona Feno [...] Anna Raffaello

Jan 5, 2023 3598 Views

Induction of Skeletal Muscle Injury by Intramuscular Injection of Cardiotoxin in Mouse

Xin Fu [...] Ping Hu

May 5, 2023 3314 Views

In vivo Electroporation of Skeletal Muscle Fibers in Mice

Steven J. Foltz [...] Hyojung J. Choo

Jul 5, 2023 1826 Views

Abstract

Our ability to move and breathe requires an efficient communication between nerve and muscle that mainly takes place at the neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), a highly specialized synapse that links the axon of a motor neuron to a muscle fiber. When NMJs or axons are disrupted, the control of muscle fiber contraction is lost and muscle are paralyzed. Understanding the adaptation of the neuromuscular system to permanent or transient denervation is a challenge to understand the pathophysiology of many neuromuscular diseases. There is still a lack of in vitro models that fully recapitulate the in vivo situation, and in vivo denervation, carried out by transiently or permanently severing the nerve afferent to a muscle, remains a method of choice to evaluate reinnervation and/or the consequences of the loss of innervation. We describe here a simple surgical intervention performed at the hip zone to expose the sciatic nerve in order to obtain either permanent denervation (nerve-cut) or transient and reversible denervation (nerve-crush). These two methods provide a convenient in vivo model to study adaptation to denervation.

Graphical abstract:

Background

Neuromuscular disorders constitute a heterogeneous group of more than 200 diseases that present impaired motor function and are often debilitating and prematurely fatal. In vertebrates, the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is a specialized cholinergic synapse with a complex molecular architecture that ensures reliable conversion of the nerve influx into muscle contraction. In various neuromuscular disorders, genetic alterations result in the failure of the neurotransmission caused by the loss of NMJs, characterized by skeletal muscle weakness and fatigue as observed in Congenital Myasthenic Syndromes, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

NMJ integrity requires both healthy presynaptic (motoneuronal) and healthy postsynaptic (muscular) compartments. The organization of the postsynaptic region relies on the heparan sulfate proteoglycan agrin secreted by motoneurons at the NMJ (Huzé et al., 2009 and references therein). Agrin binding to the LRP4/MusK complex induces Acetylcholine Receptors (AchR) clustering at the NMJs, as well as the recruitment of approximately 5 myonuclei that specialize in the expression of the genes coding for NMJs components (Simon et al., 1992; Vaittinen et al., 1999; Méjat et al., 2003; Ravel-Chapuis et al., 2007). Besides the control of postsynaptic gene expression, NMJ structural integrity require a meshwork of intermediate filaments (Mihailovska et al., 2014), linkers of the actin network such as the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (Belhasan and Akaaboune, 2020) and a precise patterning of the microtubule network (Osseni et al., 2020; Ghasemizadeh et al., 2021) that contribute to AChR addressing and clustering at the postsynaptic membrane of myofibers.

Here, we describe how to perform an efficient and rapid intervention on the sciatic nerve to create a permanent or a transient denervation. This method is adapted from standard protocols (Méjat et al., 2005; Bauder and Ferguson, 2012; Morano et al., 2018; Ghasemizadeh et al., 2021). We explain how to track efficiently the sciatic nerve allowing a simple surgical gesture involving a small incision through the skin and muscle. We propose two alternative methods for sciatic nerve injury: i) a permanent denervation (Nerve-cut), ii) a transient and reversible denervation (Nerve-crush). Each method provides specific advantages to evaluate the effects of denervation and/or monitor axon and NMJs regeneration (Morano et al., 2018; Ghasemizadeh et al., 2021).

These methods are very simple and permit the in vivo study of the neuromuscular integrity along with regeneration processes.

Materials and Reagents

Metacam®, 1.5 mg/mL oral suspension for dogs (Boehringer Ingelheim)

Ketamine, Imalgène® 1000 solution for injection (Boehringer Ingelheim)

Buprenorphine, Buprecare® 0.3 mg/mL solution for dog and cat (Axience)

Xylazine, Rompun® 2% (Bayer)

Lurocaine, solution for injection/parenteral route (Vetoquinol®)

Ocry-gel®, TVM-UK Company

PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: D1408-500mL)

Equipment

Surgical tools

Tool box (Moria, catalog number: 11210)

One pair of scissors straight pointed 10 cm long (Moria, catalog number: 4877)

Two pairs of Dumont forceps N°5 Swiss model (Moria, catalog number: MC40)

One pair of needle holder clamps (Securimed, catalog number: 100AAA100)

One pair of Dauphin’s scissors (Securimed, catalog number: 2117)

Suture thread (Ethicon, catalog number: JV390)

Hemostatic clip 1,7 cm Glolink Tool (Vetolabo, catalog number: VT-004-413-13)

Syringe 0.3 mL (BD Micro-Fine+)

Equipment

Heating Mat (Acculux Thermolux, catalog number: 461265)

Heating cabinet (ONO V.B., catalog number: RS5)

Isoflurane anesthesia (Ref VI-1586) device (TEM SEGA, MiniTag V1/Evaporator Tec7)

Fur trimmer (Moser, catalog number: VI-1586)

Procedure

Turn on the heating cabinet to allow anesthetized mice to recover properly after the procedure.

Anesthetize mouse with Isoflurane. For this purpose, place the mouse in a clean induction chamber connected to the anesthesia device (Figure 1). Adjust the isoflurane to 3–4% and the oxygen flow to 0.8–1.5 L/min. Once anesthetized the mouse loses all its tonus [For a more detailed procedure, please refer to previously described protocols (Davis, 2008)].

Figure 1. Isoflurane anesthesia set-up.Cover Mouse cornea with a drop of Ocrygel® to prevent eyes from drying-up during the procedure.

Anesthetize mouse using an intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine/xylazine mix (100 mg Ketamine/kg weight and 10 mg xylazine/ kg weight) previously diluted in a 10 mM phosphate buffered saline solution. Use a 25 G needle mounted on a 3 mL syringe.

To prevent pain due to the surgical procedure, perform a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine at the site of incision (0.1 mg/kg weight). Use a 25 G needle mounted on a 3 mL syringe.

Place the mouse on the heating mat during the whole procedure to avoid any hypothermia.

Shave the mouse at the hip (see Video 1 for the zone to shave).

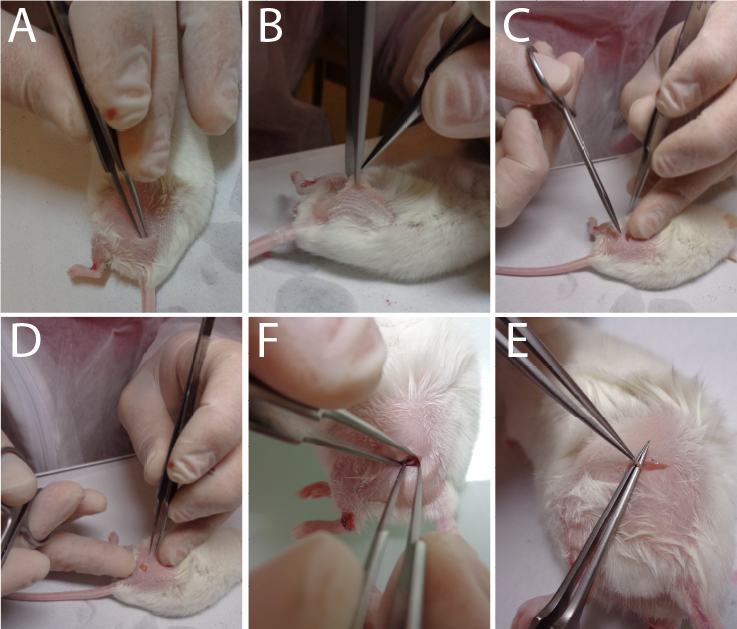

Video 1. Mouse Hair shaving process.Make a 3 mm incision in the skin over the trochanter (Figure 2A–2C) (see Video 2 to observe the approach to correctly identify the area to be incised).

Figure 2. Sequential approaches to reach the sciatic nerve.Video 2. Localization of the skin incision to correctly reach the sciatic nerve.Incise the conjunctive tissue just on the right of the hip to open a small breach through the conjunctive tissue (Figure 2D) (see Video 3 to observe the size area incised).

Video 3. Skin incision surgery.Push aside the muscular fascia in order to clearly visualize the nerve (see Video 4 to observe the extracted nerve) (Figure 2F–2E) (Caution: this must be done without any bleeding).

Video 4. Sciatic nerve isolation.Apply drops (2–3) of lurocaïne directly on the incised zone to perform a local anesthesia of the nerve. Wait at least 2 min to continue the procedure.

For definitive denervation procedure

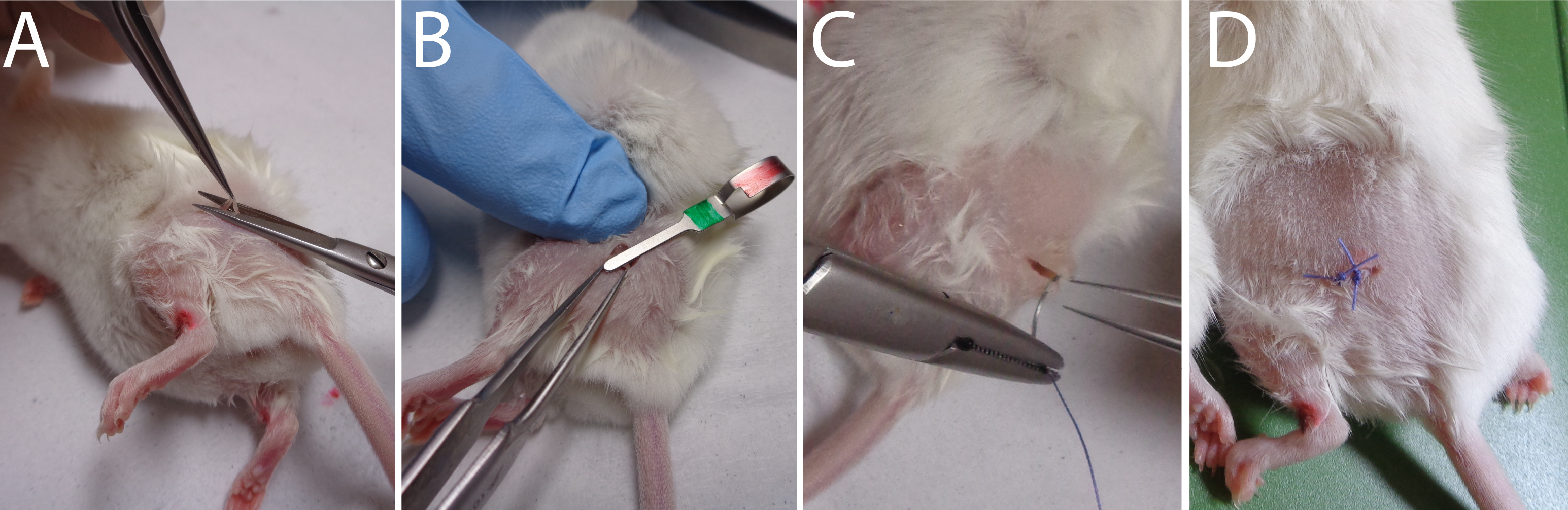

Using a fine forceps (Moria N°5 or equivalent) in order to cut a small part of the nerve (1–3 mm) (Figure 3A) (see Video 5).

For a transient denervation (nerve crush procedure)

Pinch for 30 s the exposed sciatic nerve with a hemostatic clip (Figure 3B) (see Video 6).

Video 6. Sciatic nerve crush surgery.

Figure 3. Sequential approaches to reach the sciatic nerve.Stitch the skin with one or two sutures (Figure 3C–3D) (see Video 7).

Video 7. Skin stitching surgery.Allow the mice to recover gently from anesthesia in the heating cabinet (25°C).

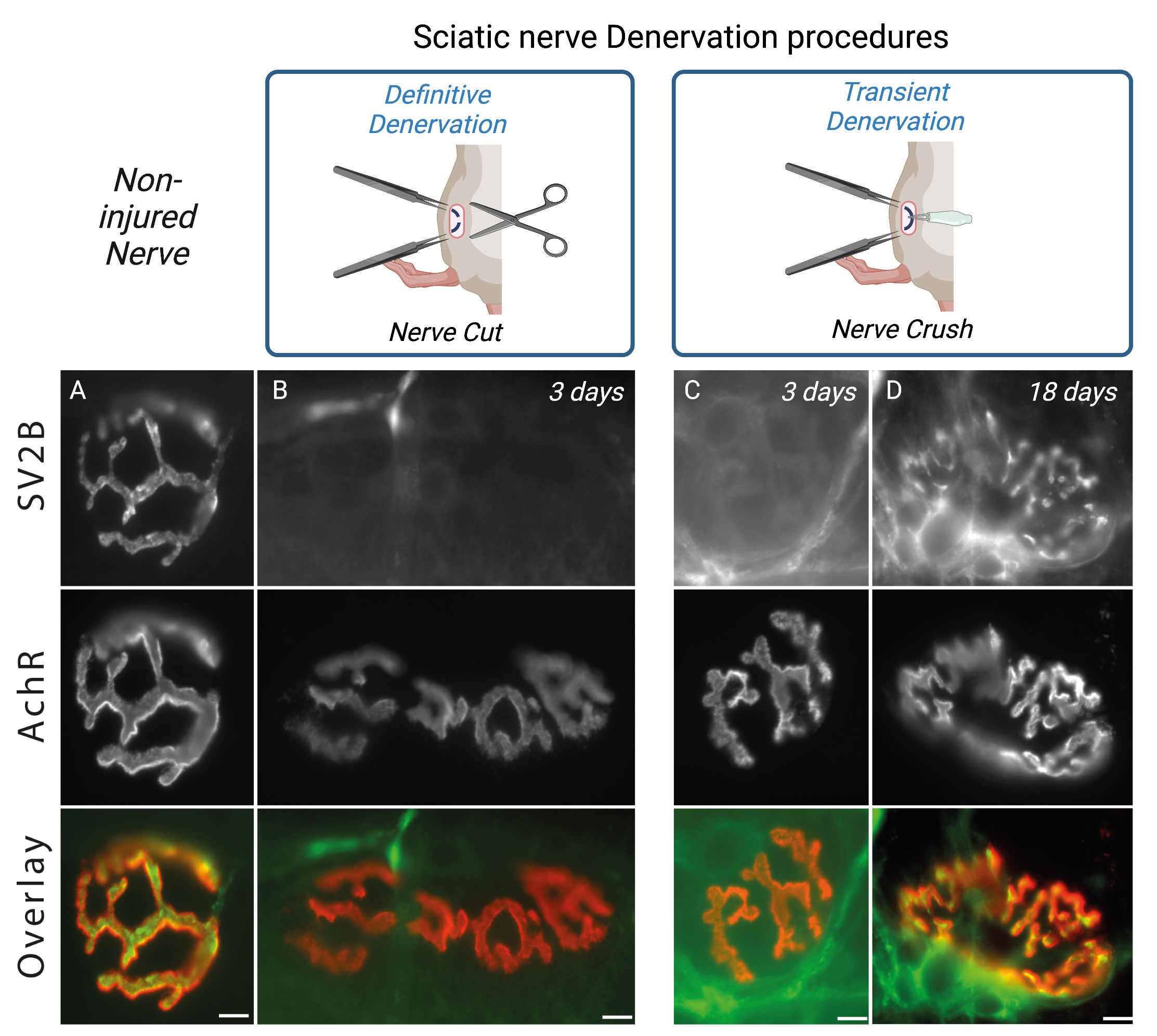

Analysis of denervation effects can be appreciated by following NMJs structural changes on Tibialis anterior isolated muscle fibers. Using immunofluorescence approaches, 3 days post-surgery you will observe the absence of SV2B labeling on isolated fibers (Figure 4A–4B). Likewise, for the nerve crush procedure, you will observe the reinnervation after 15 days as SV2B staining’s begins to progressively reappear (Figure 4C–4D). Note that the overall cross section area (CSA) of muscle fibers will decreased rapidly in the course of denervation/regeneration (Ghasemizadeh et al., 2021). Alterations of the NMJs structure such as fragmentation of AchRs, disruption of NMJs area and/or decrease of synaptic myonuclei number above the NMJs can be tracked as previously described (Jones et al., 2016; Osseni et al., 2020; Ghasemizadeh et al., 2021). Analysis of transcriptional changes by monitoring gene expression along the regeneration processes also allow characterization of the time course of NMJs alterations. mRNA or proteins encoded by genes such as MyoD (Myoblast determination protein1), Myog (Myogenin), AchR-α,β,γ,δ,ϵ (Acetylcholine Receptor α,β,γ,δ,ϵ subunits), MITR (MEF2 interacting Transcription Repressor), NRG1-α,β (Neuregulin-α,β) and MusK (Muscle skeletal receptor tyrosine-protein kinase) will be key to determine the correct time course of denervation/reinnervation (Méjat et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2015; Morano et al., 2018).

Figure 4. Sciatic nerve denervation procedure effects. Isolated fibers of tibialis anterior muscle from 2-months-old WT double-stained with an antibody against synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2B (SV2B, in green) to label the presynaptic domain of NMJs and with α-bungarotoxin–A594 (in red) to label the postsynaptic domain of NMJs. Representative immunofluorescence images of non-injured nerve (A), definitive denervation procedure (B) after 3 days and transient denervation procedure after 3 days (C) or 18 days (D). Scale bars, 10 µm.

Notes

The main difficulty lay in the precision to locate the area for skin incision (Figure 2A). You must not be too much towards the spine or the knee or both too much above the hip or buttock at the same time; otherwise, it will be very difficult to find the nerve. In fact, the nerve comes to the surface close to the skin just behind the hip as it does for you. Outside of this location, the nerve goes deep into the muscle fascia and becomes very difficult to visualize and grasp.

Note that the efficiency of the procedures is not easily visible as mice show a quasi-normal behavior after the procedure (see Video 8). Nevertheless, as a consequence of the completed procedure (Nerve-cut or Nerve-crush), after waking up, mice drag the denervated leg, as can be seen in Video 8. This situation is definitive for the Nerve-cut procedure whereas, in the case of nerve crush procedure, mice recover gradually the movement of the paw, which appears completely normal 3 weeks after the Nerve-crush procedure.

Video 8. Behaviors of mice after the procedure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from ATIP-Avenir and AFM via the MyoNeurAlp Alliance. We acknowledge contributions of the CELPHEDIA Infrastructure (http://www.celphedia.eu/), and especially the center AniRA of Lyon “Plateau de Biologie Expérimentale de la Souris”. We thank Tiphaine Dorel and members of CIQLE imaging center (Faculté de Médecine Rockefeller, Lyon-Est). All graphic abstracts were created with BioRender.com. These methods were derived from Méjat et al. (2005). This protocol was adapted from our recent work (Ghasemizadeh et al, 2021; DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70490).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Ethics

Animal experimentation: Experiments and procedures were performed in accordance with both the guidelines of the local animal ethics committee of the University Claude Bernard - Lyon 1 and French / European legislation on animal experimentation (Directive 2010/63 from European Union) approved by the ethics committee CECCAPP (agreement number D691230303 delivered by the French Ministry of Research).

References

- Bauder, A. R. and Ferguson, T. A. (2012). Reproducible mouse sciatic nerve crush and subsequent assessment of regeneration by whole mount muscle analysis. J Vis Exp (60).

- Belhasan, D. C. and Akaaboune, M. (2020). The role of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex on the neuromuscular system. Neurosci Lett 722: 134833.

- Davis, J. A. (2008). Mouse and rat anesthesia and analgesia. Curr Protoc Neurosci Appendix 4: Appendix 4B.

- Ghasemizadeh, A., Christin, E., Guiraud, A., Couturier, N., Abitbol, M., Risson, V., Girard, E., Jagla, C., Soler, C., Laddada, L., et al. (2021). MACF1 controls skeletal muscle function through the microtubule-dependent localization of extra-synaptic myonuclei and mitochondria biogenesis. Elife 10: e70490.

- Huzé, C., Bauche, S., Richard, P., Chevessier, F., Goillot, E., Gaudon, K., Ben Ammar, A., Chaboud, A., Grosjean, I., Lecuyer, H. A., et al. (2009). Identification of an agrin mutation that causes congenital myasthenia and affects synapse function. Am J Hum Genet 85(2): 155-167.

- Jones, R. A., Reich, C. D., Dissanayake, K. N., Kristmundsdottir, F., Findlater, G. S., Ribchester, R. R., Simmen, M. W. and Gillingwater, T. H. (2016). NMJ-morph reveals principal components of synaptic morphology influencing structure-function relationships at the neuromuscular junction. Open Biol 6(12).

- Méjat, A., Ramond, F., Bassel-Duby, R., Khochbin, S., Olson, E. N. and Schaeffer, L. (2005). Histone deacetylase 9 couples neuronal activity to muscle chromatin acetylation and gene expression. Nat Neurosci 8(3): 313-321.

- Méjat, A., Ravel-Chapuis, A., Vandromme, M. and Schaeffer, L. (2003). Synapse-specific gene expression at the neuromuscular junction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 998: 53-65.

- Mihailovska, E., Raith, M., Valencia, R. G., Fischer, I., Al Banchaabouchi, M., Herbst, R. and Wiche, G. (2014). Neuromuscular synapse integrity requires linkage of acetylcholine receptors to postsynaptic intermediate filament networks via rapsyn-plectin 1f complexes. Mol Biol Cell 25(25): 4130-4149.

- Morano, M., Ronchi, G., Nicolò, V., Fornasari, B. E., Crosio, A., Perroteau, I., Geuna, S., Gambarotta, G. and Raimondo, S. (2018). Modulation of the Neuregulin 1/ErbB system after skeletal muscle denervation and reinnervation. Scientific Reports 8(1): 5047.

- Osseni, A., Ravel-Chapuis, A., Thomas, J. L., Gache, V., Schaeffer, L. and Jasmin, B. J. (2020). HDAC6 regulates microtubule stability and clustering of AChRs at neuromuscular junctions. J Cell Biol 219(8).

- Ravel-Chapuis, A., Vandromme, M., Thomas, J. L. and Schaeffer, L. (2007). Postsynaptic chromatin is under neural control at the neuromuscular junction. EMBO J 26(4): 1117-1128.

- Simon, A. M., Hoppe, P. and Burden, S. J. (1992). Spatial restriction of AChR gene expression to subsynaptic nuclei. Development 114(3): 545-553.

- Thomas, J. L., Moncollin, V., Ravel-Chapuis, A., Valente, C., Corda, D., Mejat, A. and Schaeffer, L. (2015). PAK1 and CtBP1 Regulate the Coupling of Neuronal Activity to Muscle Chromatin and Gene Expression. Mol Cell Biol 35(24): 4110-4120.

- Vaittinen, S., Lukka, R., Sahlgren, C., Rantanen, J., Hurme, T., Lendahl, U., Eriksson, J. E. and Kalimo, H. (1999). Specific and innervation-regulated expression of the intermediate filament protein nestin at neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions in skeletal muscle. Am J Pathol 154(2): 591-600.

Article Information

Copyright

Osseni et al. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

How to cite

Readers should cite both the Bio-protocol article and the original research article where this protocol was used:

- Osseni, A., Thomas, J. L., Ghasemizadeh, A., Schaeffer, L. and Gache, V. (2022). Simple Methods for Permanent or Transient Denervation in Mouse Sciatic Nerve Injury Models. Bio-protocol 12(11): e4430. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.4430.

- Ghasemizadeh, A., Christin, E., Guiraud, A., Couturier, N., Abitbol, M., Risson, V., Girard, E., Jagla, C., Soler, C., Laddada, L., et al. (2021). MACF1 controls skeletal muscle function through the microtubule-dependent localization of extra-synaptic myonuclei and mitochondria biogenesis. Elife 10: e70490.

Category

Developmental Biology > Cell growth and fate > Myofiber

Developmental Biology > Cell growth and fate > Degeneration

Cell Biology > Tissue analysis > Injury model

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link