Advanced Search

Preparation of Zygotes and Embryos of the Kelp Saccharina latissima for Cell Biology Approaches

Published: Aug 20, 2021 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.4132 Views: 1251

Reviewed by: Silje Forbord

Abstract

Embryogenesis and early development in kelps are poorly studied and understood. Cultivation protocols focus mostly either on the preparation of large volumes of vegetative gametophytes or on the production of conspicuous juvenile sporophytes as starting materials for aquaculture to grow large adult organisms for biomass. Hence, our protocol describes the optimal conditions for a) efficient gametogenesis, b) synchronization of egg release, c) control of zygote density, and d) optimal embryonic development of the kelp Saccharina latissima. This species is currently subject to aquaculture development in Europe, but the aim here is to provide tools for academic research aiming to identify the mechanisms underlying embryogenesis. These protocols, adaptable to different volume scales from Petri dishes to up to ten-liter containers, are the required first steps for robust downstream experiments scaled at the cytological level (immunochemistry, microdissection, laser ablation, and cell transcriptomics) and for physiological and phycopathogenesis studies at very early stages.

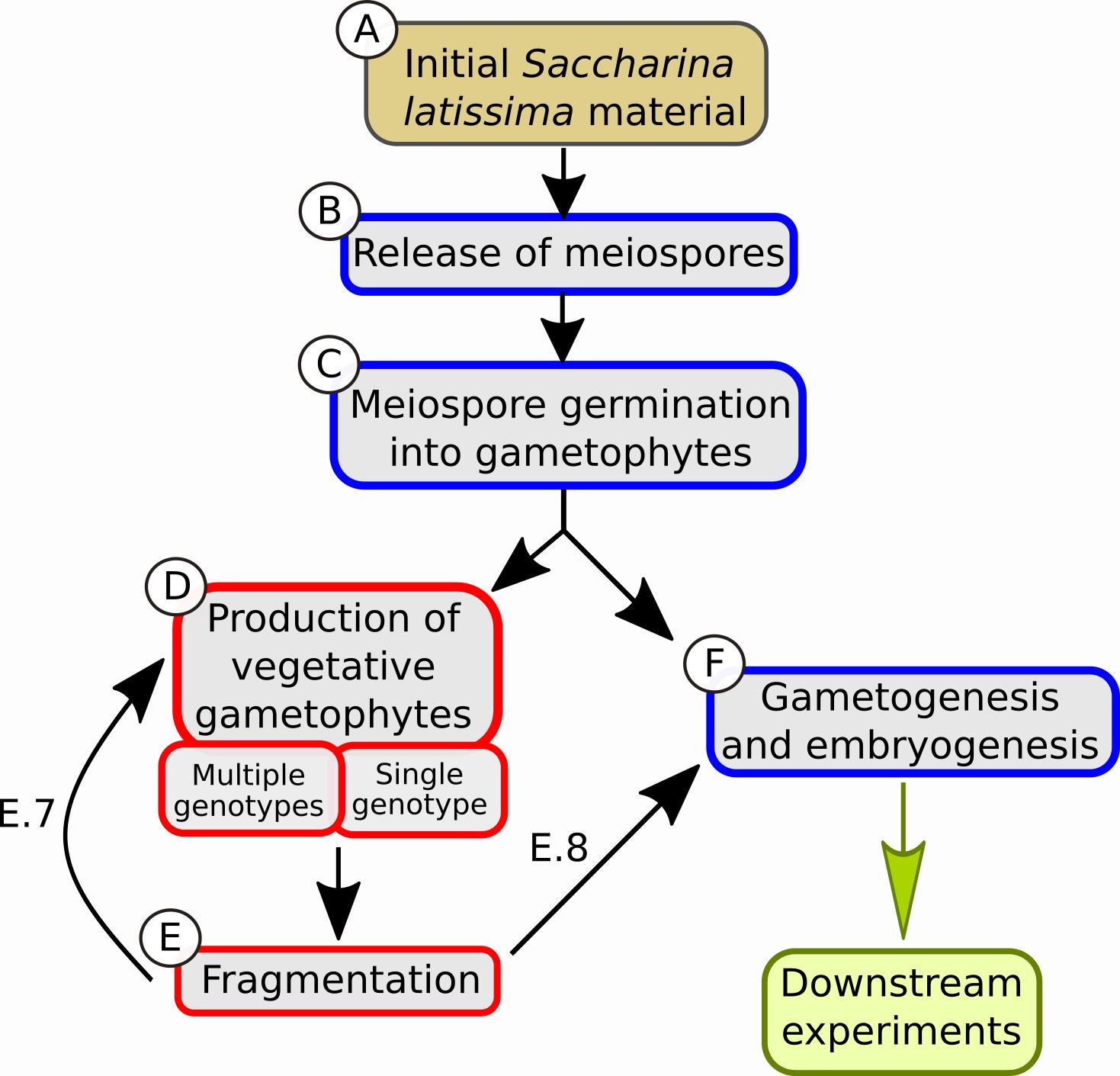

Graphic abstract:

Boxes describing the different steps of the protocol. The color of the box contours (red or blue) indicates different light conditions, red light and white light, respectively.

Background

Brown algae are a group of mainly marine photosynthetic organisms with exclusively multicellular body plans (thallus). Their thallus ranges from small filaments like in Ectocarpus species to the large conspicuous parenchymatic kelps (Charrier et al., 2012). Kelps in particular play a major ecological role as habitat for other organisms and are important primary producers in coastal ecosystems. Kelps also attract considerable economic interest, mainly as food sources (e.g., kombu). In addition, extracts from brown algae have shown anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory effects (Cumashi et al., 2007; Han et al., 2019; Long et al., 2019; Mohibbullah et al., 2019), and their biomass is used as bioethanol (Adams et al., 2009; Kraan, 2016). This altogether raises special interest in their metabolism and physiology. This is particularly the case for Saccharina latissima, as shown by an ~5-fold increase in publications over the past 10 years (from 40 in 2010 to more than 180 in 2020; Web of Knowledge), elevating it to currently being the most studied brown alga worldwide. However, this interest focuses mainly on its ecophysiology and less on its development, a balance that this protocol, in combination with expected publications, aims to improve.

The life cycle of S. latissima and kelps in general, is divided in a haploid and a morphologically distinct diploid phases (Kanda, 1936; Fritsch, 1945). During the haploid phase, the organism is prostrate and filamentous, and two sexes can be distinguished (dioicous condition). Given the appropriate conditions for gametogenesis (see next paragraph), the female gametophyte releases a spherical egg that remains fixed to the empty gametangium (also named oogonium). When the male gamete released from the male gametophyte is chemically attracted by the egg (Maier and Müller, 1986; Kinoshita et al., 2017), their fusion results in the onset of the diploid phase starting with an elongated zygote. The developing embryo will eventually grow into an impressive (>3 m) mature sporophyte after only a few months (Andersen et al., 2011). Sporiangia on the surface of the mature fertile sporophyte contain the haploid meiospores. After being released, these meiospores settle and germinate into gametophytes. While the ecophysiology of both phases is well studied (an old review: Bartsch et al., 2008), little is known about the embryonic development of the sporophytes, and historic studies only provide descriptive observations (reviewed in Fritsch, 1945). Given both the importance of this resource to the environment and as feed and food, as well as advances in science, this is expected to change. Therefore, to boost the developmental and cellular approaches aiming to decipher the mechanisms underlying embryogenesis in this alga, we propose a protocol focusing on the production and cultivation of zygotes and early embryos.

Gametogenesis is an important step for promoting normal embryogenesis in artificial culture conditions. Considerable work focused on environmental factors like light quality, temperature, and nutrients that can disrupt or inhibit gametogenesis. Lüning and Dring (1972) demonstrated that blue light induces the process while red light acts repressively. Normal white light acts like blue light, given low light intensity (Hsiao and Druehl, 1971; Lüning, 1980; Lee and Brinkhuis, 1988). Temperature is also crucial: temperatures above 15°C inhibit gametogenesis, while temperatures between 10 and 15°C are optimal (Lüning, 1980). A parameter often missed in these earlier works is density. For Saccharina japonica, high density of gametophytes inhibits gametophytic growth in in vitro cultures (Petri dishes; Yabu, 1965) and fertility at larger scales (20 L tanks, Zhang et al., 2008). Recent work from Ebbing et al. (2020) further clarifies the density parameter and the effect of its combination with light quality, a correlation not considered in previous works. Specifically, gametogenesis-induction by blue light occurs only in low-density cultures combined with low light intensity. Red light has the opposite effect. In high light intensity, red light promotes higher fertility than blue light or white light. Regarding nutrients, high concentrations of chelated iron into the culture medium seem to promote gametogenesis in other kelp species (Motomura and Sakai, 1984; Lewis et al., 2013). Considering the above parameters, the present protocol relies on the biological properties of different light conditions in combination with the concentration of nutrients in the medium to either arrest or promote gametogenesis.

In addition, this protocol allows the production of zygotes and embryos amenable to downstream experiments, like immunolocalization protocols, in which the steps of chemical fixation, cell wall digestion, antibody incubations, and staining can occur inside glass bottom Petri dishes. Alternatively, and depending on the size and the developmental stages of embryos, embryos can be transferred onto manufactured or homemade poly-L-Lysine (1 mg ml-1) coated slides or coverslips using tweezers with thin ends. In transmission electron microscopy (TEM) protocols, while fixation and post fixation steps can occur in common plastic Petri dishes, dehydration requires incubation in acetone, which would dissolve most plastic Petri dishes. Therefore, material transfer into, e.g., Falcon or Eppendorf tubes or glass Petri dishes before dehydration and infiltration will be necessary in this case.

Finally, the protocol describes how to control the density of growing embryos, which impacts the production of i) healthy embryos, ii) embryos sufficiently spread to allow subsequent monitoring of ,e.g., growth dynamics in time-lapse observation, and iii) embryos amenable to isolation and experimentation, e.g., through microdissection and laser ablation.

Clean (close to sterile) conditions are essential through the entire protocol, especially during gametogenesis induction and embryogenesis.

Altogether, this protocol will promote further studies on the microscopic stages of kelp development.

Materials and Reagents

1.5 ml sterile Eppendorf tubes

Sterile scalpel

Filter tips 1,000 μl, 100 μl, and 20 μl (Starlab, TipOne)

Plastic Petri dishes Ø35 mm (Sarstedt, catalog number: 82.1135.500)

Petri dishes with glass bottom Ø28.2 mm (NEST, catalog number: 801001)

Pellet pestles, blue polypropylene (autoclavable) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: Z359947-100EA)

Cell scraper (Sarstedt, catalog number: 83.1830)

Cell strainer 40 μm (Falcon, catalog number: 352340)

Autoclaved, 0.2-5 μm filtered seawater (SW), stored at 14°C

Counting chamber slides (Kova glasstic slide 10 with counting grids, catalog number: 87144)

Pasteur pipettes, long

Nalgene bottles, 2 and 10 L

H3BO3

FeCl3

MnSO4

ZnSO4

CoSO4

EDTA

(NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O

NaNO3

C3H7Na2O6P

Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin)

Thiamin (vitamin B1)

Biotin

Tris

Provasoli solution (see Recipes)

Equipment

Inverted Microscope Leica DMi8, light source: CTR compact, camera: RGB Leica DMC4500

Laminar flow hood

Light source: Philips, Master TL-D 18W/865, commercial sheet of red filter (LEE filters, 026 Bright Red)

Climate chambers with controllable temperature and light source

Automatic pipettes: 1,000, 100 or 50, and 10 μl

Lighter

Procedure

Category

Plant Science > Phycology > Cell isolation and culture

Developmental Biology > Reproduction

Cell Biology > Cell isolation and culture > Organ culture

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link