- Home

- Protocols

-

BGC identification and clustering using automated genome mining software

Biosynthetic genes were predicted and annotated in all the genomes using the automated genome mining pipeline implemented in AntiSMASH (antibiotics & SM Analysis Shell, v7.0 [50]), which identifies BGCs based on probabilistic models (HMMs). The predominant class of BGCs identified by AntiSMASH includes those containing the following core genes: polyketide synthases (PKSs), non-ribosomal peptide synthases (NRPSs), terpenes, ribosomally-synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), and hybrid BGCs. BGCs identified via AntiSMASH exhibit varying degrees of similarity to a characterized BGC present in the MIBiG repository (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster) and to each other. MIBiG is a repository comprising standardized entries for experimentally validated BGCs of known function from different domains of life, e.g., bacteria, fungi and plants [51].

To compare gene sequences and BGCs identified via AntiSMASH and identify homologous and widely distributed BGCs, we used the biosynthetic gene similarity clustering and prospecting engine or the BiG-SCAPE program ([52], https://git.wageningenur.nl/medema-group/BiG-SCAPE). BiG-SCAPE builds sequence similarity networks for each BGC class. Within each network, similar BGCs are grouped into gene cluster families (GCFs) and two or more GCFs potentially encoding structurally similar compounds are grouped into clans. Each network (terpene, PKS or NRPS) therefore contained several GCFs and clans (Fig. 1B). The number of clans detected for a network also depends on the clustering threshold employed, with lower cut-offs implying a stricter clustering threshold, leading to fewer connections and vice versa. We generated the BGC network by applying raw distance cutoffs of 0.20, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.80. To prevent overestimation of potentially novel BGCs, we chose the network with a cutoff of 0.6. The analysis was performed by retaining singletons and using the PFAM (protein families, v37.0 (21,979 entries, 709 clans)) database [53].

The gene network of each biosynthetic class was inspected for the presence of widely distributed BGCs. Among the clans obtained for each network, the largest GCFs/clans were obtained for terpenes (represented by Clan1 and Clan2 in Fig. 1B). The core genes of the two clans were identified based on similarity to a characterized biosynthetic gene in the MIBiG repository. This analysis suggested that the core genes of both widely distributed BGCs are SQSs, which are involved in the synthesis of cholesterol/ergosterol. We then continued with in-depth analyses of the two terpene clans to identify them in silico and explore their diversity, homology and synteny across LFF.

The widely distributed terpene BGCs were not detected by BiG-SCAPE for some species. We first verified if this observation could simply be an artefact of sequencing technology or BGC prediction and clustering algorithms as the absence of otherwise conserved genes in a taxon indicates major evolutionary impacts. To fish out the other SQS BGCs in our dataset that did not group within Clan1 and Clan2, we implemented a twofold approach. First, we investigated whether there were other clans in the terpene network that had an SQS as the core gene. Second, we performed local BLAST using the SQSs of Clan1 and Clan2 as queries and searched them in a database composed of all the terpene synthases of the species in which no SQS was detected by BiG-SCAPE (using a 30% sequence similarity threshold). When no SQS was detected for a taxon in the database, we further validated the absence of the SQS in that taxon by aligning the raw sequencing reads with the Clan1 and Clan2 SQSs. If no reads aligned to the SQS of Clan1 or Clan2, this was considered evidence for the absence of this BGC in that taxon.

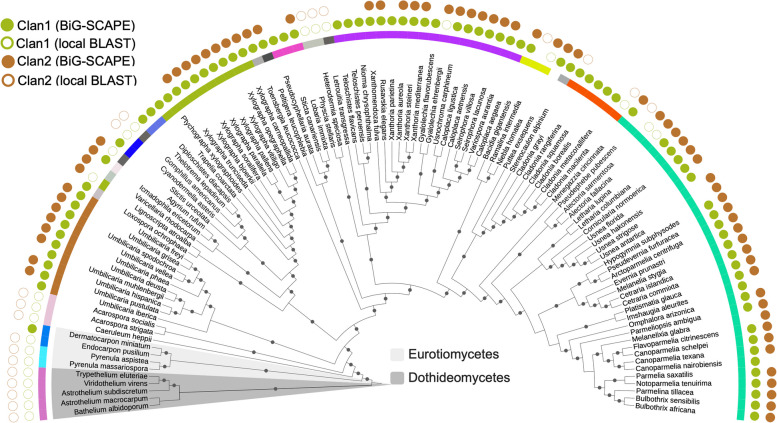

The combined results, i.e., the presence/absence and distribution of SQS BGCs of both clans across LFF as detected by BiG-SCAPE and based on local BLAST, were visualized using iTOL (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic distribution of the two conserved SQS BGC clans. A cladogram depicting the distribution of Clan1 and Clan2 in LFF, as shown in Fig. 1B, and in the outgroup taxa. Dots on the branches indicate bootstrap support > 70. The empty circles outside the cladogram denote the species in which the BGC/core gene was not detected by BiG-SCAPE but rather by the local sequence similarity search using the sequence of the core gene (similarity threshold > 80%). A total of 75.67% of the species (84 species in total) contained two SQS clusters, one belonging to each clan. The core gene in the BGCs of both clans is a putative SQS, but the two clans contain different accessory genes. The Dothideomycete and Eurotiomycete SQS BGCs, however, were phylogenetically most distant and shared low conservation with those of lichenized fungi belonging to the class Lecanoromycetes. Based on this evidence, we propose that Clan2 might be restricted to lichenized fungi. However, a broader sampling is required to confirm this observation. On the other hand, Clan1 is conserved in LFF but also shared by some closely related non-lichenized fungi

Do you have any questions about this protocol?

Post your question to gather feedback from the community. We will also invite the authors of this article to respond.