- EN - English

- CN - 中文

Qualitative Detection of Lipid Peroxidation in Mosquito Larvae Using Schiff’s Reaction: A Simple Histochemical Tool for In Situ Assessment of Oxidative Damage

基于席夫反应的蚊幼虫脂质过氧化定性检测:一种用于原位评估氧化损伤的简便组织化学方法

发布: 2026年02月05日第16卷第3期 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5597 浏览次数: 83

评审: Anonymous reviewer(s)

Abstract

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) is a major indicator of oxidative stress and cellular damage, frequently associated with environmental and toxicological stressors and mechanistically linked to ferroptotic regulated cell death (RCD). This protocol describes a simple and reproducible method for the qualitative in situ visualization of LPO in mosquito larvae using Schiff’s reagent, which histochemically labels reactive aldehyde groups [such as malondialdehyde (MDA)] generated during lipid degradation. Although Schiff’s reagent detects aldehydes commonly associated with lipid peroxidation, these compounds are not exclusive to LPO and may also arise from other oxidative processes. The method preserves tissue integrity, enabling direct, spatially resolved observation of oxidative damage in whole larvae. Following staining, larvae are rinsed in a stabilizing sulfite solution to maintain the characteristic magenta coloration. Using this assay, Culex quinquefasciatus larvae exposed to ferroptotic cyanobacteria, such as Synechocystis sp., exhibit a marked accumulation of lipid-derived aldehydes consistent with lipid ROS–mediated damage. This oxidative response is specifically suppressed by pre-treatment with the canonical ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), which inhibits lipid peroxidation and significantly reduces larval mortality. As a complementary approach to traditional spectrophotometric assays such as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), this qualitative method enables in situ visualization of lipid peroxidation without tissue homogenization, providing a rapid and biologically informative screening tool for assessing ferroptosis-associated oxidative damage in Cx. quinquefasciatus and other biological models exposed to multiple stressors.

Key features

• Direct qualitative assessment: Provides visual, histochemical evidence of lipid peroxidation in situ, enabling rapid evaluation of oxidative membrane damage at the tissue and whole-organism levels.

• Preservation of spatial context: Allows localization of oxidative damage without tissue homogenization, maintaining tissue architecture and spatial resolution.

• Environmental and toxicological screening: Optimized for rapid detection of oxidative stress in mosquito larvae exposed to larvicides, biocontrol agents, and other environmental stressors.

• Complementary to quantitative assays: Functions as a screening tool that complements spectrophotometric methods such as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS).

Keywords: Oxidative stress (氧化应激)Graphical overview

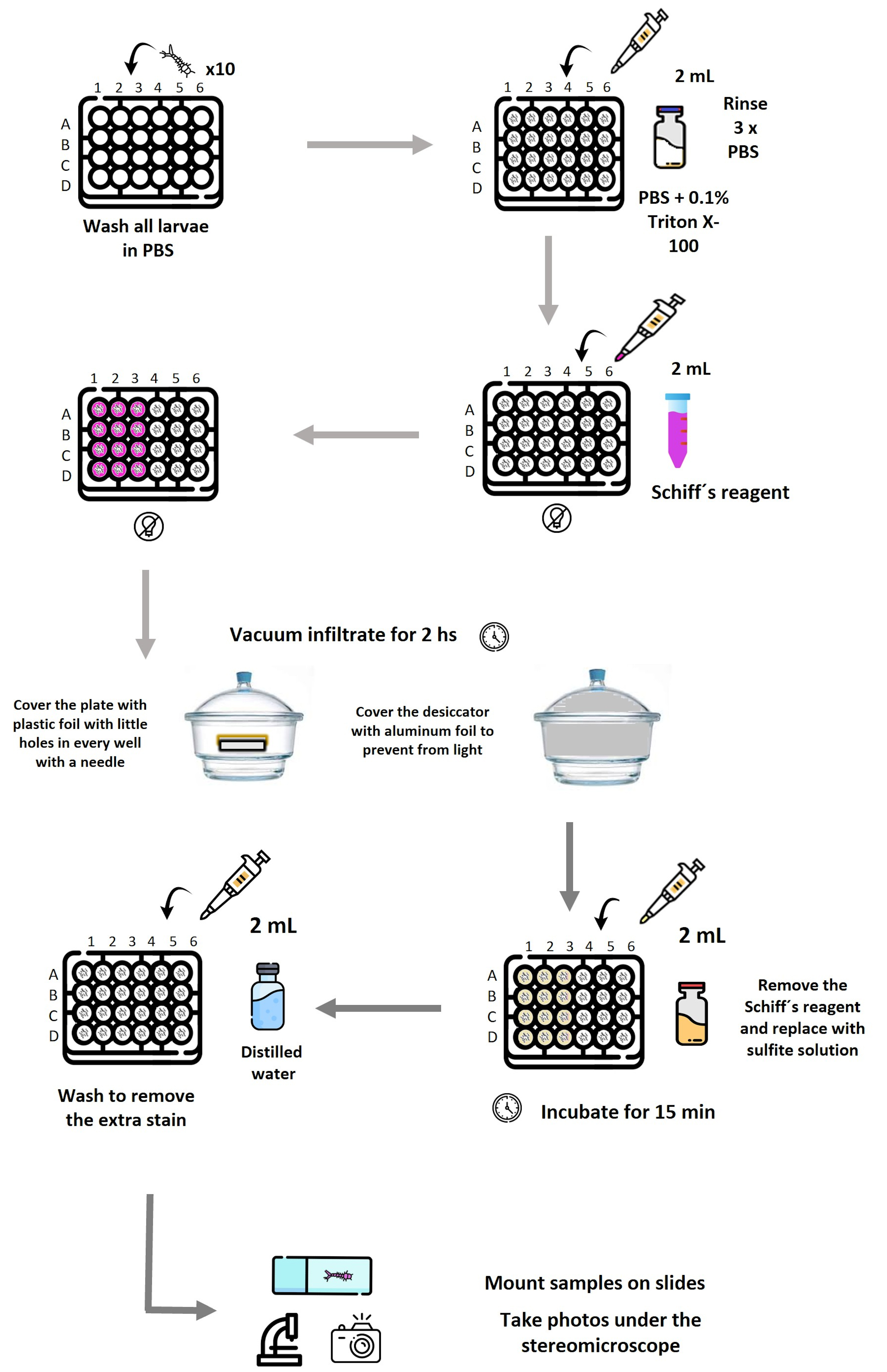

Schematic representation of the workflow used to detect lipid peroxidation–associated aldehydes in mosquito larvae by Schiff’s reaction. Larvae (10 per well) are distributed in a 24-well plate and washed in PBS, followed by permeabilization with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and subsequent PBS rinses. Schiff’s reagent is added where needed. The plate is covered with Parafilm, with holes in each well. Vacuum infiltration is applied in a desiccator covered with aluminum foil for 2 h to enhance reagent penetration. After staining, Schiff’s reagent is removed and replaced with sulfite solution to stabilize the coloration, followed by washing with distilled water to remove excess stain. Larvae are then mounted and photographed under a stereomicroscope. Reagent volumes (2 mL), incubation times, and light-protection steps are indicated at each stage. Plate layout: Row A, negative controls; A1–A3, stained with Schiff’s reagent; A4–A6, processed without Schiff’s reagent (unstained). Row B, positive controls exposed to 100 mM H2O2; B1–B3, stained; B4–B6, unstained. Row C, larvae exposed to live Synechocystis; C1–C3, stained; C4–C6, unstained. Row D, larvae exposed to ferroptotic Synechocystis; D1–D3, stained; D4–D6, unstained. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Background

The evaluation of oxidative stress and cellular damage is essential in fields such as toxicology, environmental biology, and insect physiology. Lipid peroxidation (LPO), the oxidative degradation of membrane lipids, represents a key biomarker of cellular damage induced by stressors, toxins, or pathogens [1].

In mosquitoes, LPO detection is particularly relevant for assessing oxidative stress induced by insecticide exposure and for understanding physiological mechanisms underlying tolerance or susceptibility. The thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assay remains a widely used quantitative approach to detect malondialdehyde (MDA) and requires tissue homogenization [2,3].

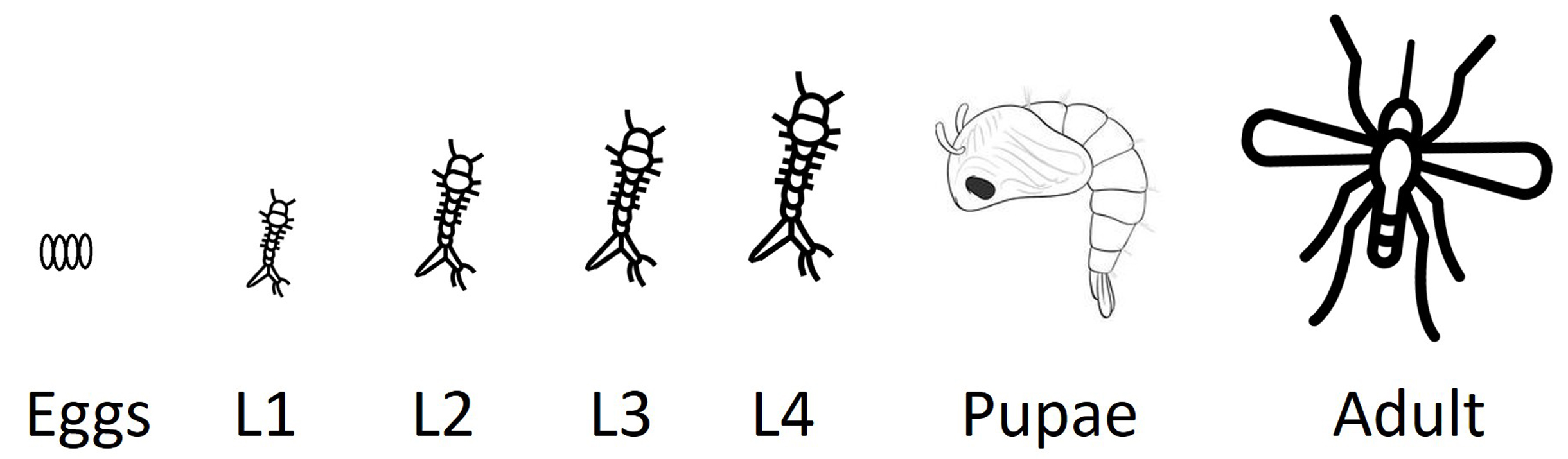

As a complementary approach that overcomes the limitations of TBARS-based analyses, this protocol employs Schiff’s reagent, a histochemical staining technique that permits the in situ localization and visualization of aldehyde functional groups, producing a visible magenta coloration upon reaction. It is crucial to note that while Schiff’s reagent detects reactive aldehydes generated by lipid peroxidation [such as malondialdehyde (MDA)], these aldehydes are not exclusive to LPO and may also arise from the oxidation of alcohols or the oxidative degradation of carbohydrates and amino acids under stress conditions [4]. Consequently, this staining provides a qualitative in situ assessment of oxidative damage and requires careful interpretation within the experimental context and the inclusion of appropriate controls [5]. The methodology, originally adapted from Awasthi et al. [6], has been specifically optimized for mosquito larvae, successfully preserving tissue architecture and enabling whole-organism visualization of oxidative damage patterns. The southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus) undergoes four distinct developmental stages—egg, larva, pupa, and adult—with the larval stage representing a fully aquatic, metabolically active phase particularly suitable for assessing oxidative stress responses. Under optimal conditions, development from egg to adult occurs within approximately 7–10 days, and the size of the larva increases as it molds to a new instar (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Life cycle of the southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus).Schematic representation of the mosquito life cycle, including egg, four larval instars (L1–L4), pupa, and adult stages. The protocol described here is optimized for the analysis of lipid peroxidation in larval stages, which represent a fully aquatic, metabolically active phase, particularly susceptible to oxidative stress induced by environmental and toxicological stressors.

Materials and reagents

Biological materials

1. Mosquito larvae at the stage of interest; in our study, second-stage larvae (L2) (Figure 1)

Reagents

1. Distilled water

2. Schiff’s reagent (Biopack, catalog number: 2000938600- 100 mL)

3. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) (Biopack, catalog number: 9632.08)

4. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: H1009)

5. Sodium metabisulfite (Na2S2O5) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: S9000)

6. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (Anedra, catalog number: 71690)

7. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) (Mallickrodt, catalog number: 6984)

8. Disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4) (Fluka, catalog number: 71645)

9. Monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4) (Timper, catalog number: 6504)

Laboratory supplies

1. Standard 24-well flat-bottom microplate made of optically clear polystyrene

2. Microscope slides (Sail Brand, catalog number: 7102)

3. ParafilmTM M plastic wrap

4. Aluminum foil

Solutions

1. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (see Recipes)

2. Permeabilization solution (see Recipes)

3. Schiff’s reagent staining solution [6] (see Recipes)

4. Sulfite solution 0.5% (w/v) (see Recipes)

5. BG11 medium (see Recipes)

Recipes

1. PBS

| Components | Quantity | Final concentration |

| NaOH (sodium hydroxide) | 0.4 g | 200 mM |

| KOH (potassium hydroxide) | 0.01 g | 3.57 mM |

| Na2HPO4 (disodium phosphate) | 0.072 g | 10.14 mM |

| KH2PO4 (monopotassium phosphate) | 0.001225 g | 0.18 mM |

| Sterile Mili-Q Water | To 50 mL |

2. Permeabilization solution

Add 0.1% Triton X-100 to PBS (Recipe 1).

This solution increases cell membrane permeability, allowing reagents to penetrate into cells or tissues.

3. Schiff’s reagent staining solution [6]

Prepare a 10% (v/v) Schiff’s reagent solution in distilled water and mix well. Prepare fresh.

4. Sulfite solution 0.5% (w/v)

Na2S2O5 in 0.05 M HCl.

5. BG11 medium

| Component | Quantity |

| NaNO3 | 1.5 g |

| K2HPO4·3H2O | 0.04 g |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.075 g |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.036 g |

| Citric acid | 0.006 g |

| Ferric ammonium citrate | 0.006 g |

| EDTA (disodium magnesium salt) | 0.001 g |

| Na2CO3 | 0.02 g |

| Trace metal mix A5 + Co* | 1 mL/L |

| Deionized water | 1,000 mL |

| pH (after autoclaving and cooling) | 7.4 |

* Trace metal mix A5 + Co contains (in g/L) H3BO3 2.86, MnCl2·4H2O 1.81, ZnSO4·7H2O 0.222, Na2MoO4·2H2O 0.390, CuSO4·5H2O 0.079, and Co(NO3)2·6H2O 0.0494

Equipment

1. Pipettes (Gilson PIPETMAN, FinnpipetteTM, 2-20, 20-200 and 100-1,000 μL)

2. pH meter (pH Tutor, Eutech Instruments)

3. Weighing balance (Sartorius, 0.1 mg to 220 g)

4. Vacuum pump and vacuum desiccator (SIGMA, model: Z119008)

5. Stereomicroscope (Nikon, model: SMZ800 stereoscope)

6. Digital camera (Olympus, model: DP72 with CellSens Entry imaging software)

7. Orbital shaker (Haimen Kylin-Bell Lab Instruments Co., Ltd., China, model: TS-8)

8. Brush (Artística Dibu, Marta 100 series, size 5/0, Argentina)

9. Insulin syringe needle (Micro-Fine, catalog number: 328418)

Procedure

文章信息

稿件历史记录

提交日期: Oct 28, 2025

接收日期: Dec 30, 2025

在线发布日期: Jan 15, 2026

出版日期: Feb 5, 2026

版权信息

© 2026 The Author(s); This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

如何引用

Cuniolo, A., Berón, C. M. and Martin, M. V. (2026). Qualitative Detection of Lipid Peroxidation in Mosquito Larvae Using Schiff’s Reaction: A Simple Histochemical Tool for In Situ Assessment of Oxidative Damage. Bio-protocol 16(3): e5597. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5597.

分类

环境生物学 > 环境毒理学

细胞生物学 > 组织分析 > 组织染色

您对这篇实验方法有问题吗?

在此处发布您的问题,我们将邀请本文作者来回答。同时,我们会将您的问题发布到Bio-protocol Exchange,以便寻求社区成员的帮助。

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link